The Trial: Part 5

Rudy Kurniawan’s Trial

A Multi-Part Feature on the trial of Rudy Kurniawan, including the transcripts, testimony and evidence that put the largest wine counterfeiter of our time behind bars.

THE TRIAL - PART 5

DAY 4: THURSDAY 12TH DECEMBER (CONTINUED)

Witness: Aubert de Villaine

The Government called Aubert de Villaine as a witness, who used a federally approved interpreter, Isabelle Duchesne, to give his testimony. de Villaine is the co-manager at Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, in Burgundy. He gave the history of the domaine, which came into his family in 1869, where it has remained ever since. He also clarified that there is the appellation Romanée-Conti, which is one vineyard wholly owned by the Domaine, and there are other vineyards or parcels owned by the Domaine which are bottled under the vineyard or parcel name and the name Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (DRC). The total area of the domaine is 28ha. DRC makes seven Grand Cru wines. Two (Romanée-Conti and La Tâche) are monopoles. They also have parts of Richebourg, Grands Echezeaux, Corton and others, which are shared with other growers. They make a very small amount of wine that is not Grand Cru – maybe 2% of their production. de Villaine, born in 1939, began working at it in about 1964, when he was 25. He started from scratch, working in the vineyards, and in 1974 was named co-manager, which he has been ever since.

de Villaine then explained the history of phylloxera in France, and how this affected the Romanée-Conti vineyard, which was replanted after the 1945 harvest. The 1945 harvest was only two barrels – 600 bottles in total. At the domaine, there are no more bottles of 1945. He doubts very much whether there are any real bottles left.

They then discussed reconditioning. de Villaine noted that there are several levels. For example, if the label is damaged, you might just replace the label. But if the wine has had a problem – if there has been excess ullage for example – then the bottle might be refilled with a bottle of the same wine. To do this, one bottle would be sacrificed to refill others. DRC did this for some prized customers, but they stopped about 15 or 20 years before the trial, because they realised the bottles were being reconditioned in order to be sold – in other words, for speculation – and as a grower he makes wine for being drunk, not for speculation. Therefore, he stopped reconditioning.

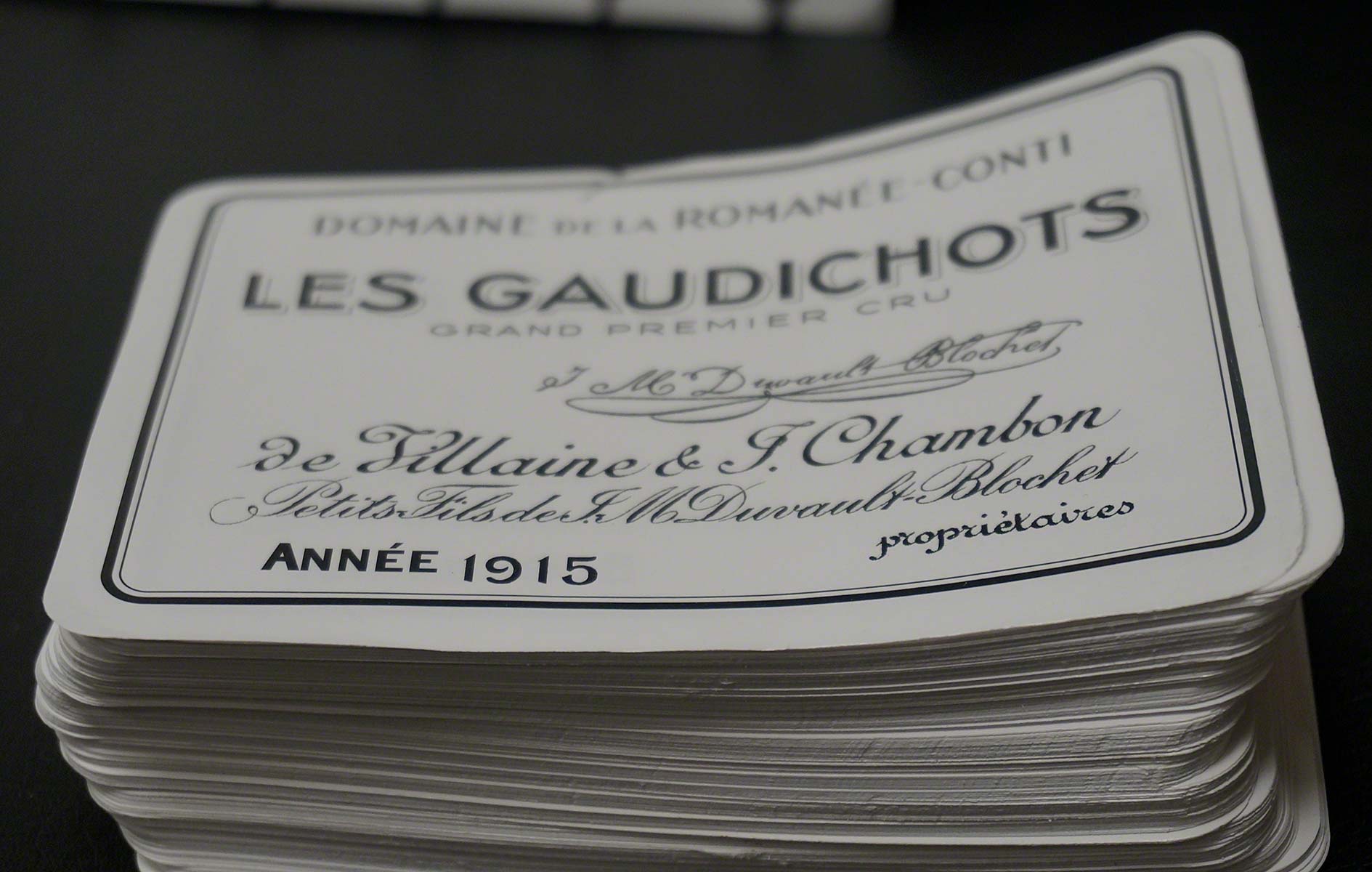

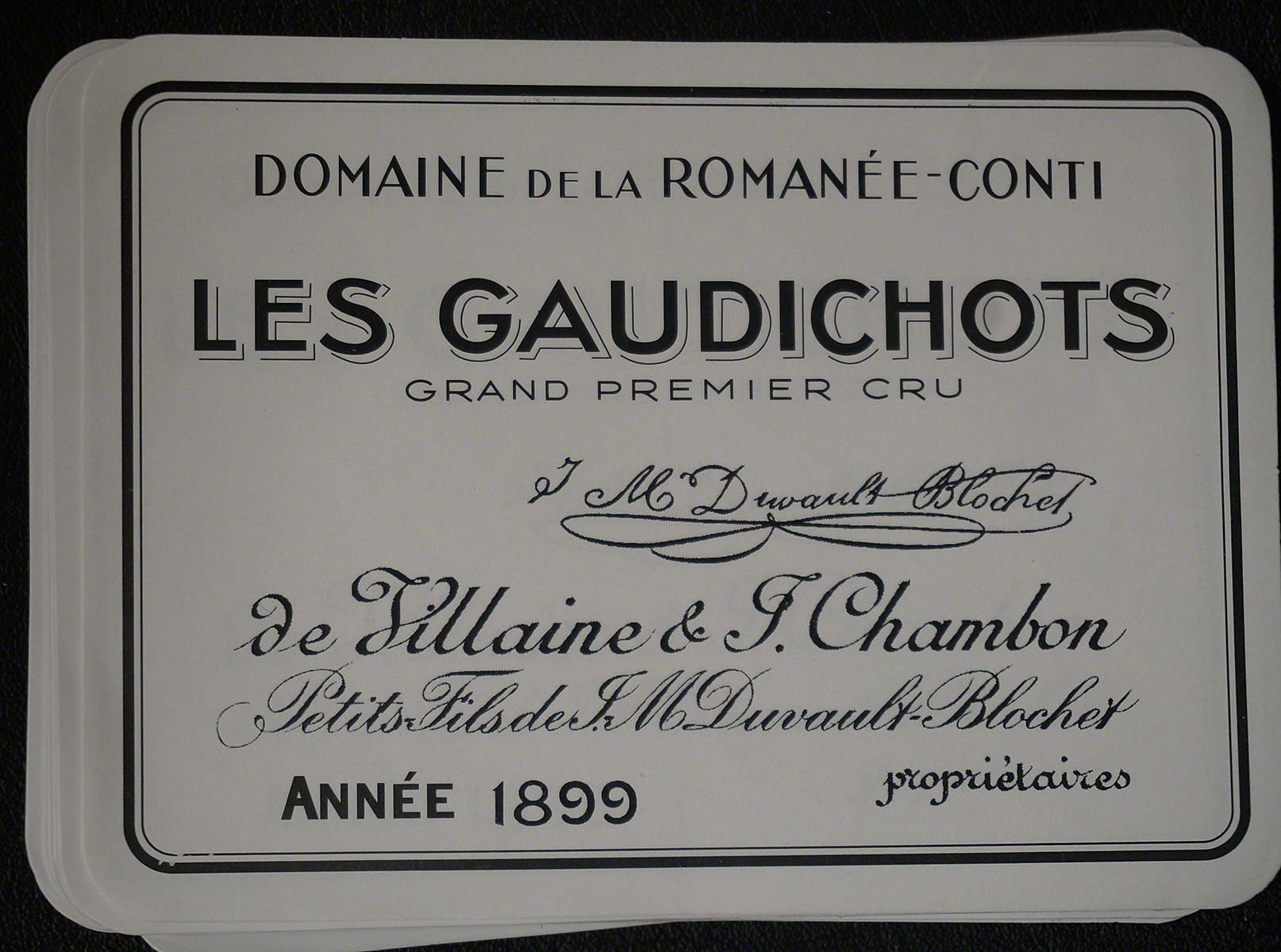

Facciponti then showed de Villaine a set of stacks of labels, and he was initially quite overcome. These were all, for a start, great vintages, like 1915.

At DRC, they do not keep labels like this any more – they keep labels as long as they have the wines, but these, they do not have. If they did, they would never be for sale, but just family treasures that they would drink sometimes. He described seeing stacks of several hundred labels for vintages that don’t even exist any longer as wines as being like for a movie. He commented that they never had any of these self-adhesive labels – ever.

Gaudichots was a Premier Cru until 1931 when it was attached to La Tâche, at which point it ceased to exist. And de Villaine noted that this kind of wine, if it existed, would be extremely sought after by collectors because it’s something extremely, extremely rare. He had never seen an 1899 label for Les Gaudichots.

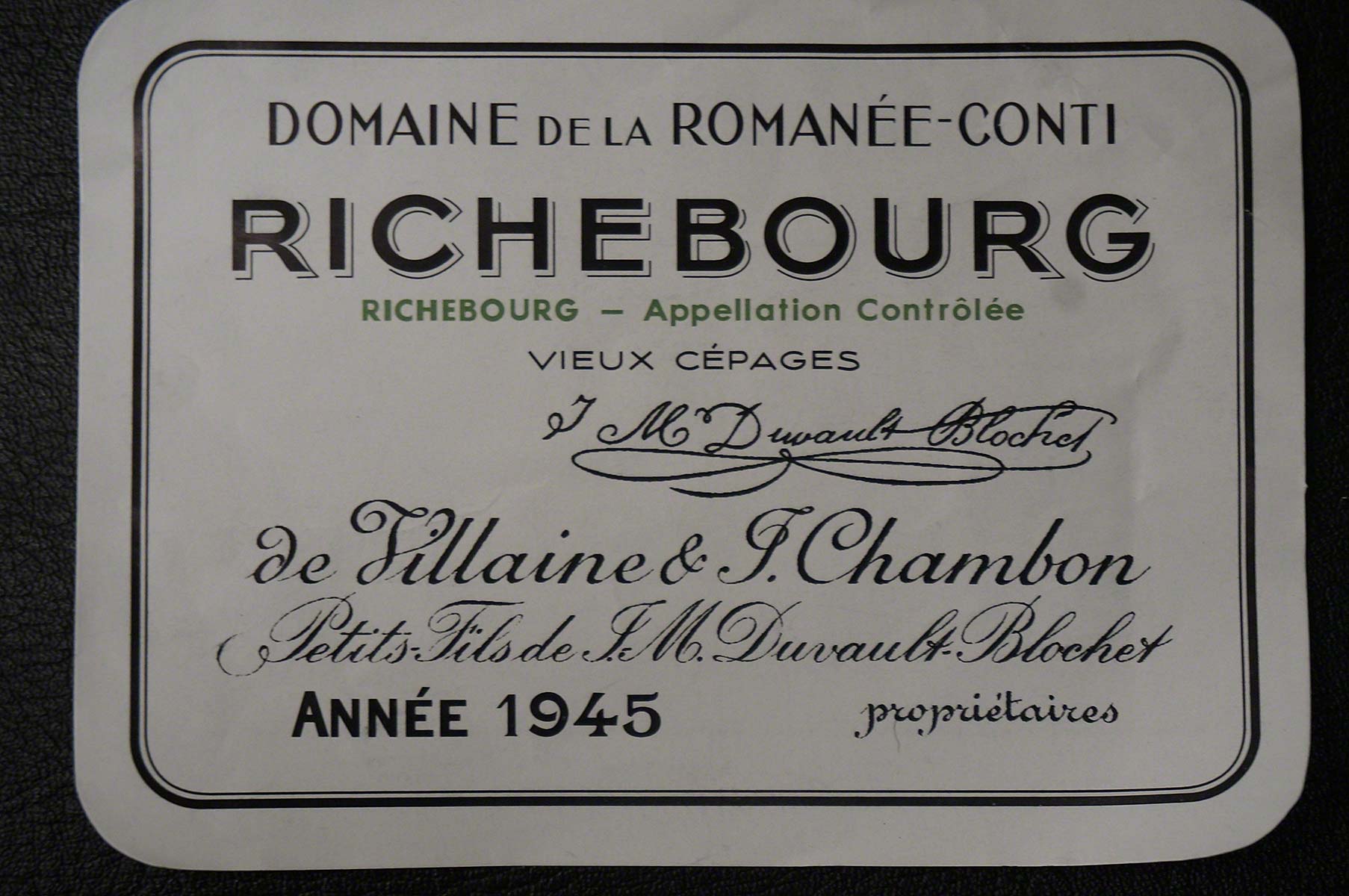

Richebourg VC 1945

He also examined a label for Richebourg Vieux Cépages, a small part of the Richebourg vineyard that did not succumb to phylloxera until 1945, when it was making about 200 to 300 bottles a year. It had been printed on one side 1945 and on the other 1942.

de Villaine said that based on what he had seen, he knew these were not the Domaine’s labels. The Domain had never used a laser printer to print its labels, and he confirmed that Rudy Kurniawan had never been authorised to print labels for the Domaine.

Aubert de Villaine, cross-examination

Mooney picked up the 1942 / 1945 label, and asked if DRC had ever printed labels on both sides. de Villaine replied that the domaine did not need to save paper that much. Mooney stated that it was unlikely that anyone would ever expect this to be something that would be put on a bottle, a statement with which de Villaine heartily agreed.

de Villaine confirmed he knew of the company Nicolas, a long time wine merchant. He confirmed that there was a period when, like most Burgundian domaines, DRC was selling wine in bulk to ship to Nicolas, for them to bottle, which was done until the 1930s. However, Romanée Conti itself was only ever sold in bottle. Hand blown bottles were phased out at least 100 years ago.

de Villaine noted that they have a certain library of labels, but some have disappeared. He added that it’s only very recently that there has been the scale of problem with fake bottles they are currently encountering. He confirmed that they do not label the bottles before shipping, because the cellars are damp and the labels would be damaged.

The oldest bottle of wine in the DRC cellars is one bottle of Richebourg 1911 – unlabelled. Mooney said that if he wanted to buy it, DRC would put a label on it. de Villaine replied it was out of the question (despite Mr Mooney’s semi-serious plea to negotiate). Mooney added that he presumed the same was true of more recent wines, from, for example, the 1970s.

Mooney then asked further questions about reconditioning, and de Villaine added that they do it sometimes at the domaine for their own wines – using one bottle of six to refill the other five, and then drinking the remainder. They do this if the quality of the cork is in question. However, he stressed that the best thing to do with a wine like that is to drink it; even reconditioning it is hard on the wine.

Mooney wondered if, having opened a bottle of wine, tasted a bit, he could put a cork back into it to drink it later. de Villaine said that this was a very very temporary measure, because in old bottles such as the ones under discussion, the wine may oxidise in just an hour or two. If it’s opened, it should be drunk.

Mooney queried whether de Villaine had met Rudy Kurniawan, and he replied yes, and then said “Hello Rudy”. He did not recall the dates, but did remember meeting him. de Villaine had signed a bottle “très cordialement, Aubert”, which he was often asked to do for people. When asked if he brought the bottle to the tasting, M de Villaine replied that he frankly had no memory of it, so would not have brought the bottle.

Mooney showed M de Villaine another bottle, of 1945 Romanée-Conti, which he also did not remember, that had been signed by a number of people including, again, Aubert de Villaine. M de Villaine thought this must have been from a big tasting done in New York some years ago. de Villaine agreed this bottle had been appreciated by everybody, although he did not specifically remember Allen Meadows rating it 100.

They discussed tasting notes and (much as Christophe Roumier had stressed) Aubert de Villaine emphasised that these were personal notes. He also stressed that the wine changes in the bottle, and notes for a 1990 La Tâche written in August 2008 would not necessarily still be relevant in December 2013 (i.e. the time of the trial).

Mooney asked Aubert de Villaine if he remembered a tasting in December 2005, a vertical tasting of La Tâche in New York. M de Villaine replied that his memory has become weak now, much weaker than it used to be, and he doesn’t even remember anything of this tasting, where he was supposed to be present. Mooney said “and you were present”, and M de Villaine replied it was possible. de Villaine then, when told it was at Per Se, contradicted Mooney to say “But wasn’t it a Romanée-Conti tasting?” (Rumours of his forgetfulness possibly being overstated…). Mooney asked if he saw Rudy Kurniawan there, and if he knew that Rudy was supplying wine. He replied that he did not know about the wine, but that if Rudy was there, he would have seen him. He also agreed it was possible that Wilf Jaeger supplied wine, as he had a “great cellar”. Mooney queried how M de Villaine could not remember “that it was one of those wine tasting events that was written about and that people are still talking about”, at which point Aubert de Villaine delivered the most wonderful line, saying “Well, I’ve been to a few of them, so, you know, I don’t remember them all.” He acknowledged that he thought he would remember if there were wines he suspected of not being authentic, and he did not recall any from this tasting.

Aubert de Villaine, re-direct

Facciponti led the redirect. His first question was whether M de Villaine would be surprised if someone said they had six bottles of 1945 Romanée Conti. Aubert de Villaine replied he would be very surprised. When you have a production of 600 bottles in a vintage, with a wine that has been so sought after, one wonders how it could be possible to have one person with six bottles. It seems “very complicated”.

Joseph Facciponti then asked why fake bottles are a problem for the domaine. M de Villaine replied it is destructive – it puts a cloud of doubt on the authenticity of the wines, and that cloud of doubt is the beginning of the loss of reputation – of the domaine and of Burgundy in general.

There was a brief recess, while Judge Berman remarked to Counsel that he knew one of the individuals, Josh Leuchtenberg, named on one of the signatures of one of the bottles that Mooney submitted as evidence. He didn’t know him well – and had never share a bottle of wine, never mind of 1945 Romanée-Conti, with him, but felt he should disclose it. Both lawyers confirmed Leuchtenberg was not a witness. They all agreed that New York is a very small town, and that people don’t realise what a small town it is.

Click here for Part 6.