The Trial: Part 12

Rudy Kurniawan’s Trial

A Multi-Part Feature on the trial of Rudy Kurniawan, including the transcripts, testimony and evidence that put the largest wine counterfeiter of our time behind bars.

Day 6: Monday 16th December

Witness: Michael Egan

The Government then called Michael Egan, a fine wine expert originally from London who now lives in Bordeaux. He authenticates people’s wine collections, both private and professional, and advises people on the purchasing and storage of their wines. After a degree in English literature and history at Manchester University, he did a one year course in Bordeaux on tasting wine and understanding winemaking. He also has the WSET Diploma, the details of which he explained. He confirmed that he was testifying as an expert witness, hired by the US Government.

Egan started in the wine trade at Oddbins, and joined Sotheby’s in 1981. He has specialised in fine and rare wine since 1982, and received training in wine authentication from Sotheby’s. He started as junior administrator, moving on to junior cataloguer, senior cataloguer, deputy director and then became director in 1999. He left Sotheby’s in 2005. He worked for himself from 2005, and then joined a Bordeaux negociant, Bordeaux Wine Bank, in 2010, as director of authenticity and auctions, where he worked until 2012. In 2006 he started an authentication service advising clients worldwide concerning purchase and sale of their wines.

While at Sotheby’s, where he was for 23 years, he was involved in an average of about 10 auctions a year. Over the time he was there, he was actively involved in authenticating wines, which he described as primarily a visual inspection. He first looks at the bottle to make sure that it is in good condition, for example that the level is not too low, which would indicate poor storage. He looks at the condition of the label, the cork, the bottle. From this he can determine whether the wine is in good condition, and whether or not it is authentic. His tools include a flashlight, a magnifying glass and a jeweller’s loupe. When examining a bottle he looks for signs that the label is authentic – is it the right print quality, does it look like it is as originally supplied to the winery, is it the correct cork, and does the wine look like the same period as the purported vintage. Over his career he has probably examined tens of thousands of bottles.

Egan left Sotheby’s when his father, who was half French, died, leaving him a share in a house in Bordeaux. He moved to Bordeaux with his family and bought out his cousin’s share, seeing it as the ideal opportunity to do what he had always wanted to do, to live in the area they make the wine. Since he left Sotheby’s, wine authentication has been more or less his full time job, using the same process as he used when at Sotheby’s. He has also lectured on wine authentication, particularly to wine professionals in the US and the Far East. He has also previously testified in court, in New York earlier in 2013. At that time he was testifying in the lawsuit filed by Bill Koch against Eric Greenberg, and he confirmed that the judge in that case allowed him to testify as an expert witness.

At this point, Jason Hernandez moved to allow Egan to testify as an expert in the fields of fine and rare wines, wine auctions and authentication. The application was granted.

Egan then addressed the jury to tell them why he was there. He confirmed that he had been employed by the US Government to review bottles and other items that had been sold or presented for sale by the defendant, and to offer his opinions about them. He had studied 267 bottles, the vast majority of which he had found to be counterfeit. He had also reviewed other items, which he believes have been used to fabricate such counterfeit items. His fee for the case, given its complexity, will be about €18,000. The reason it is so high is because of the “sheer density and proliferation of exhibits” that he had to review.

At the request of Hernandez, Egan then briefly explained the working of a wine auction to the jury. The main factors affecting the price are the condition of the wine, the authenticity of the bottle, and finally the condition of the label. He confirmed that it matters absolutely that the labels, the cork and other aspects of the wine bottles are authentic. The wine something the chateau takes great pride in producing, and the capsule and seal, for example, are guardians of the wine therein. Therefore, if the capsule or cork has been compromise or manipulated, that is a serious issue. The label is also a guarantee that what is in the bottle corresponds to the production of that particular property, vineyard and year. So these authenticity questions are very important.

He confirmed that if a bottle or any part of it had been altered by someone other than the domaine, that would render the wine worthless. If there had been any changes to the physical features or the contents of a bottle, an auction house would want to know, as would the buyer.

Egan then explained “bin soiled label”, which means that the label has been affected by damp or dust or mould. He stressed that this has nothing to do with the quality of the wine – a lot of very good cellars are damp and the label gets bin soiled, but it’s very good for the preservation of the cork and thus the wine inside the bottle. Auction houses mention it because some buyers will make a decision to buy based on the quality of the label. A corroded capsule also matters to buyers, but they are well aware that old and rare wines acquire this patina over time. This is a thing that they would expect as a normal occurrence.

Provenance, according to Egan, is the history of a wine bottle. Five star provenance, for example, would be buying directly from the chateau. If you are not the first in line in this way, a history of provenance is very important. If you can establish a chain of custody, you have a history of the provenance. Wines of sketchy or poor provenance might not even make it into an auction catalogue. For example, a wine that has travelled around the world a few times – it will probably have aged faster than it should have done, and will not be as desirable a purchase. Provenance is important to both buyers and sellers at an auction. Good provenance helps a seller get the best possible price for the bottles, and buyers will often compete with each other to buy those wines with the best provenance.

Egan testified that in his experience, the majority of serious wine collectors kept records of their rare-wine purchases. If someone made most or all of their money buying or selling wine, it was more likely they would keep records because that is their livelihood, and in order to perform good administration, they need to have good records.

Egan then testified that between the period 2002 and 2012, the fine and rare wine auction market grew exponentially. In 2002 it was worth around $92m; by 2007, it was worth $300m, the rise being driven by increases in both value and volume. There was, during this time, a particular increase in interest in old and rare Burgundy. Many of the clients for this type of wine were also clients of Egan. They are generally wealthy, and compete with each other at auction to buy these bottles whenever they come up for sale.

Hernandez then asked Egan if, given his over 30 years’ experience, he knew how counterfeit wines were made. Egan explained that there are a number of methods, varying from the simple to the very sophisticated. The easiest is to have two bottles of the same Chateau – e.g. 1983 and 1982 Pétrus. Drink the bottle of 1982, soak the labels off both bottles, and put the 1982 label back on the 1983 bottle. At first glance, all seems well, although the cork will still have 1983 embossed on it.

The next step would be to remove the capsule as carefully as you can, remove the cork with an “Ah So”, and chip or scratch off the 3 to make it a 2, then reinsert the cork and put the capsule back on.

The most sophisticated way is to start completely from scratch. You have to acquire all the basic components of a bottle of wine: the empty bottle; the label, photocopied or printed, but probably not the original; the cork; the means to brand a cork; the capsule; adhesive to put the label onto the bottle. You need to make sure the bottle is of the right period of the purported wine, and then you fill it with whatever you want, put all the pieces onto the bottle, and there it is.

The liquid inside may or may not be wine – it could be anything. That is one of the dangers of buying a counterfeit wine. If a counterfeiter is looking to the long term, however, looking to maintain or build business, then it needs to resemble to a certain extent the real thing. If it is supposed to be a wine from the 20s, then a wine from the 20s or so needs to go in. As wine matures, it throws a sediment and the colour changes – for a red wine from a dark red to a light garnet. So the counterfeit wine, through visual inspection, needs to look roughly the same. The taste has to emulate the era. With rare wines, there will also be the fact that not many people have actually tasted this particular wine, so there may not be a benchmark for comparing the counterfeit to the real thing. The “donor wine” will be of far less value than the real thing – probably no more than 10% of the value. It is also normally a concoction – a blend of different wines, with perhaps some aromatics to try and emulate the flavour of a real wine. Younger wines can be used to freshen up an older wine.

Egan described a good taster who has the experience and palate to be able to distinguish one wine from another, one region from another, one vintage from another. Usually, this is honed through detailed tasting notes and understanding what the wines mean. A producer of counterfeit wines who wanted to have an ongoing business would need to be a good taster, and an aptitude for blending wine in order to make a good representation of the real thing.

Hernandez asked whether Egan had an opinion on whether any of the bottles that were sold or consigned by Kurniawan were counterfeit. Egan replied that he did have an opinion, and that it was that “almost all, with very few exceptions, of these bottles are counterfeit”. He also said that his opinion was that much of the evidence he had reviewed in the case was material for the manufacture of counterfeit wine. He had looked at roughly 19,000 bottle labels, stamps for corks, vintage stamps, serial number stamps, corks, blank corks, bags and bags of capsules, adhesives, ink pads, sponges to apply substances to labels, and a great variety of counterfeit import and vintage labels.

Egan added that his opinion would not change if he were not allowed to rely on the evidence seized from Kurniawan’s home. In reviewing other documentation, he has seen that there have been orders for large supplies indicative of counterfeiting, requests for a large quantity of empty bottles, invoices and emails concerning the purchase of cheaper wines from less desirable vintages that would not normally be part of Kurniawan’s purchasing activity.

Egan then used a PowerPoint presentation to explain some of the opinions he had reached in the case. It started with counterfeit labels, and he used examples taken from Exhibits 14-1 and 14-3.

The first image was a label that has been Photoshopped so that everything has been removed apart from the edge. The next image is a number which has been scanned and applied to that label. On the bottom row, there are close-ups of the border of the outside frame of the label. These images were all on Kurniawan’s computer.

Egan then showed an image of one scanned image, and a number of other scanned images surrounding it, that have been used to manipulate an existing label to make it whatever you want. The main label does not have a vintage on it, so that had been Photoshopped out, as Romanée-Conti doesn’t do labels without vintages. The signatures change, depending on the era. Up until a point Mme Bize-Leroy and Aubert de Villaine we co-owners, and then Mme Bize-Leroy left and M de Villaine became the sole proprietor.

He then showed an image from Kurniawan’s computer that were neck labels for DRC, for either La Tâche or Romanée-Conti. These are high quality images, probably to be sent to a printer. The vintages in question: 1957, 1945, 1962, were excellent.

Egan then looked at four labels of La Tâche. He pointed out that if you look at the top of the label, there is the same indent on the paper, meaning that they are the same label, but different vintages. He called this a clone – a way of replicating one label and turning it into another. He believed the original to be 1949, and the counterfeit 1945.

The court then looked at four Romanée-Conti labels, from 1943, 1937, 1939 and 1945. The 1943 is a scanned image of a real label; Egan pointed out a sort of scuff mark around the “année” on the bottom left hand corner. This has been scanned, and then used to create the other labels, and the vintage substituted. The little scuff mark is identical on all four images. He showed other examples of cloning, such as 1942 and 1945 Romanée-Conti labels with the same blemishes, highly improbable in real life. Given the rarity of the 1945, he believed it was the 1942 that was the original, and the 1945 created from that. He then showed a version of an older Romanée-Conti label, which had had the vintage removed. The next slide showed the same label with 1911 added, and then 1919 and 1921, all with the same “base label”. He then showed four labels of Romanée-Conti from 1923, 1934, 1929 and 1936. 192 and 1934 are other images taken from the computer, and he then demonstrated how that could have been done.

Egan then showed the same thing with Domaine Roumier. He demonstrated that with an authentic label, scanned in, but the vintage then Photoshopped out. There were then examples without the address, or the vintage, or other text below Bonnes-Mares. He commented that this is a very sophisticated way of creating a counterfeit label.

There were then images of counterfeit vintage labels, in the process of being prepared. These images were typical of older vintage labels used by Domaine Ponsot and Domaine Roumier. There was an example of a 1949 vintage label, which was a clone of one image, multiplied nine times.

There was then a Ponsot Close de la Roche label, in very high definition. Egan believed this was a real Ponsot label scanned into the computer, which would then be tidied up and sent off to the printer.

There was a label for Chateau Pétrus, 1947 – a highly desirable and very rare wine. It would be particularly rare in a large format.

There were then three labels from Comte Georges de Vogüe. Egan noted that the serial number had six zeroes, and he commented that he would find it highly improbable that a domaine would start their run of numbers with a zero; it would always start with a one.

Egan then noted the Nicolas stamp at the bottom left, which he thought was a mistake. Egan believes that this is normally found around the vintage. Egan explained that Nicolas was a négociant, who were famous from the 1920s to 1988 for having the best wine. Their philosophy was not to release their wines into the market until 10 years after the vintage. The fact that they were known for having great wine, and the hearsay that they didn’t apply labels until the bottles were released made it a counterfeiter’s paradise, because they can produce the fake label, and say that the reason it is so new is because it is Nicolas stock. Egan then showed an image of the Nicolas stamp, and then a contact sheet of the labels Nicolas put on their wines when selling to overseas customers, and a scan of the instruction to decant the wine, “ce vin dôit être décanté”. Egan added that a buyer thinking he was getting a Nicolas wine would think the provenance was very good, because Nicolas were very careful how they stored things.

Egan then moved on from labels to corks. He showed a number of images taken from Rudy’s computer, showing a number of vintages in different fonts. These were images that could be sent to a manufacturer asking him to produce stamps that exactly replicate the vintages on that sheet. Once the stamp is produced, it is put onto an ink pad, and then applied to the cork. The majority of the vintage images were both old and very good.

Corks often also have some branding from the producer, and Egan showed the court brands for three different Bordeaux chateaux: Pétrus, Cheval Blanc and de ‘Eglise. All three were typical of 1920s, although there was an error on the Pétrus, shortening it from Propriete to P-R-O-P-R-E. These templates are then sent off to the manufacturer who would create a stamp that can be stamped onto the cork.

Egan then showed the court stamps from DRC, including ones from 1937 and 1945 era, which would have been most lucrative. He explained why 1945 in particular was so famous for DRC, because it was the last year of ungrafted vines. He also showed an image of a Montrachet stamp, noting that they actually had the stamp that was created from this template, and the cork that was stamped with it. There were also images from Domaine Ponsot and from Chateau Latour.

At this point, Egan stepped down from the witness box and moved to the Exhibit table. He began by looking at Exhibit 1-401

This was a bottle that purported to be 1945 Romanée-Conti, found at the defendant’s home. Egan chose this as a good example of how the counterfeiting process was done, because the label, the shoulder label, and the export label are reproductions, and the wax on top is modern. He then examined Exhibit 1-401A, which he described as “like a model kit”, all the parts needed to make the fake bottle of ’45 Romanée-Conti.

Egan started with the label on the bottle, pointing out that it had been weathered, treated to look old. He demonstrated that the loose label was exactly the same scale and dimensions as the one on the bottle, and that there were 35 to 40 of these at Kurniawan ‘shouse.

He then demonstrated that the shoulder label, as supplied by the printer, had also been treated to give a semblance of age. It too, was exactly the same as the loose shoulder label.

Egan then showed the jury the loose wax tablet, which was one of several ordered by the defendant, and showed them exhibit 1-233, a cup of wax melted, so it could be applied to the top of the bottle, and a DRC seal applied to it. He noted the quality difference in the application – Michael Egan has seen many such fakes, and none manages to get the wax properly applied.

He then picked up the import label, Selection Raymond Beaudouin, which were not the original label. It too had been treated beforehand to look old.

He concluded that this was a very good example about starting the counterfeit bottle from scratch.

Egan then looked at two further bottle, 1-402 and 1-402A, both found at the defendant’s house.

The first was a counterfeit bottle 1899 Romanée-Conti, but in this case, Michael Egan thought that it was an original bottle with the label taken off, and a fake label applied. In contrast to the previous bottle, it had not been rewaxed. The second was very similar, and also an old, hand-blown bottle. It had handwriting on it saying “1899 RC? Or 1875?”, which Michael Egan believed meant denoted the bottle could pass as either r1875 or 1899. He noted that these were original bottles from Burgundy, pre-1914, both hand blown with a deep punt, and no seam. He then showed the jury another similar “counterfeiting kit” for these wines.

Egan then moved onto Exhibits 1-406 and 1-407.

Exhibit 1-406 was a Marcassin PinotNoir, which retails for about $200 in Sonoma. On the bottle it says “40s/50s DRC”, which Mr Egan took to mean that he was going to use it for producing 40s or 50s DRC. Egan did not think it would be used entirely as a substitute, but that a proportion would be added to the concoction. In contrast, Exhibit 1-409 was a Burgundy, a 1990 Gevrey-Chambertin from Labouré Roi, which Mr Egan described as a “pretty good producer” but not in the same league as the ones in question in the trial, such as Ponsot, Roumier or DRC; it is a lot cheaper. This also has “40, 50 DRC”, which would also be a notation of an ingredient of the concocted blend for DRC.

Exhibit 1-408 was a Duckhorn, from Napa, a Cabernet Sauvignon Merlot blend. It says “40s to 60s Pomerol/Graves”, which Egan took to be it would be an indication in the production of counterfeit Bordeaux from that era.

Egan then looked at a half-bottle, that from the notations he thought was made up of 2/3 Palmer 1961, 1/3 Palmer 2000, and a bit of something else he could not identify. It has been crossed out, which implies it’s a blending bottle that has been used before, and there were further notations, implying it had been used for other blends, including a Mouton Rothschild 1045, a very rare and expensive wine from a great vintage.

Egan then examined a set of stamps, including six he had selected to illustrate his testimony. These are for numbers 20,399; 20,406; 20,395; 20,397; 20,398 and 20,402. Government Exhibit 14-1 was then shown, which had an image of bottles of Mouton Rothschild. Egan confirmed that these numbers corresponded exactly to the stamps on the labels, and the ink colour is the same. He knew them to be counterfeits, for one reason because the colour was not as deep as the true Mouton-Rothschild ink. Egan concluded that the stamps in evidence were the actual stamps used for applying the numbers to the labels, and as such, are counterfeit.

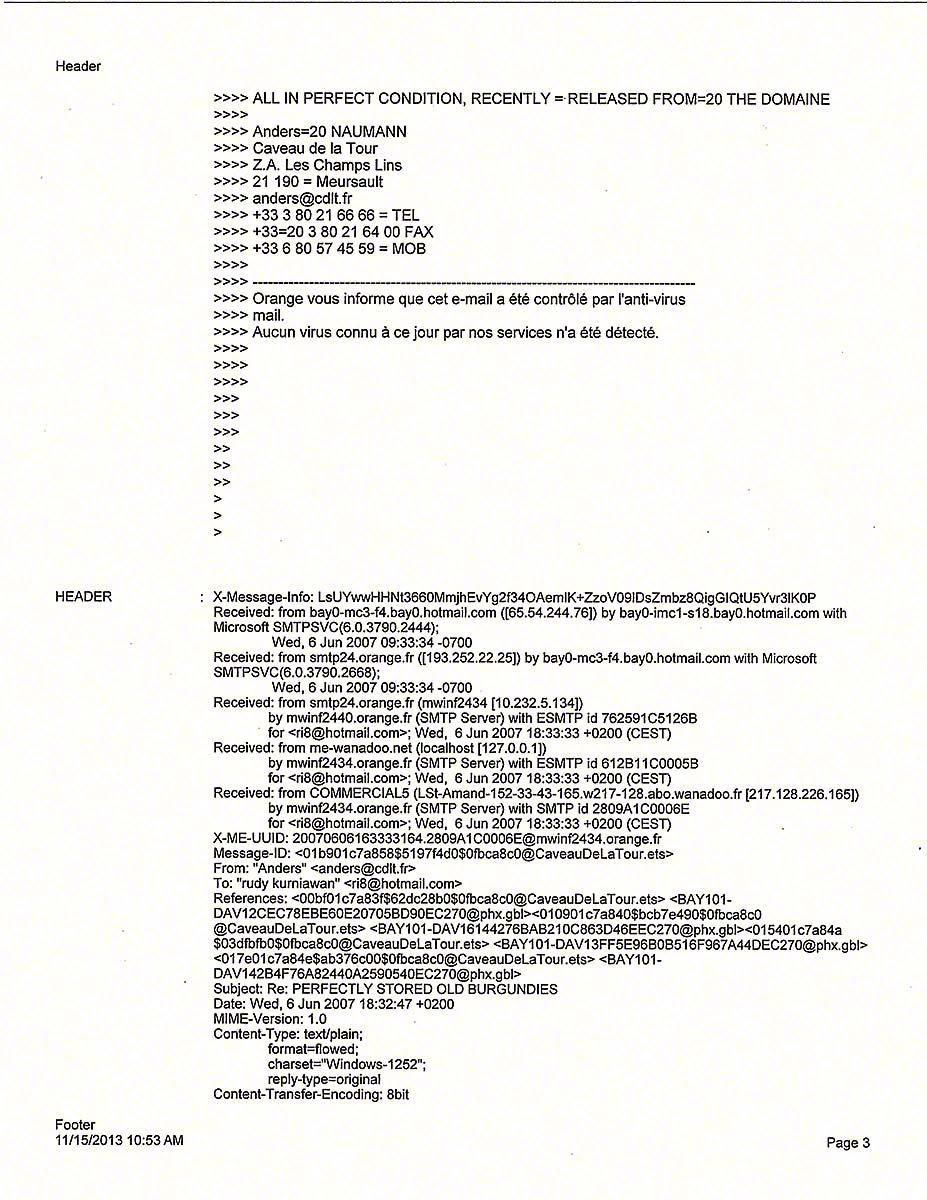

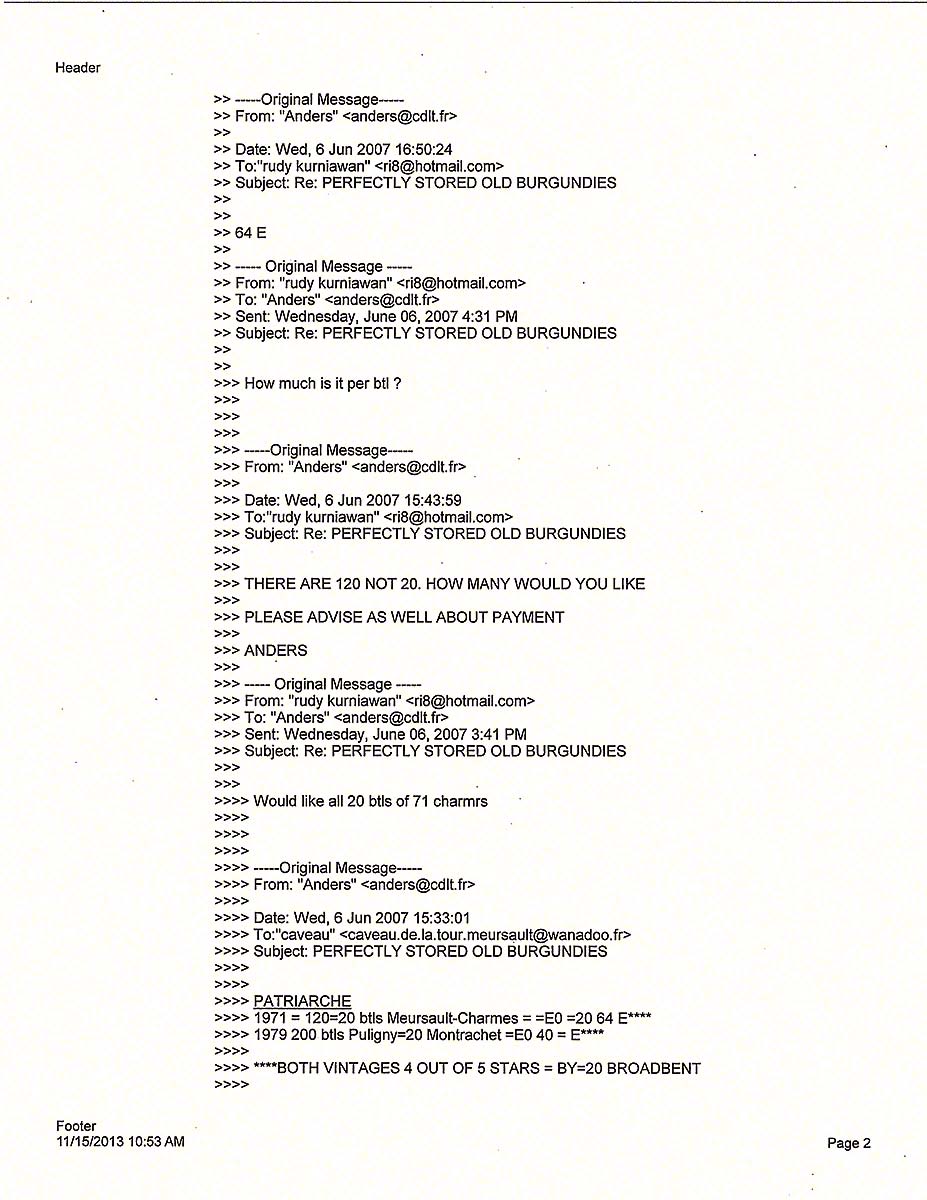

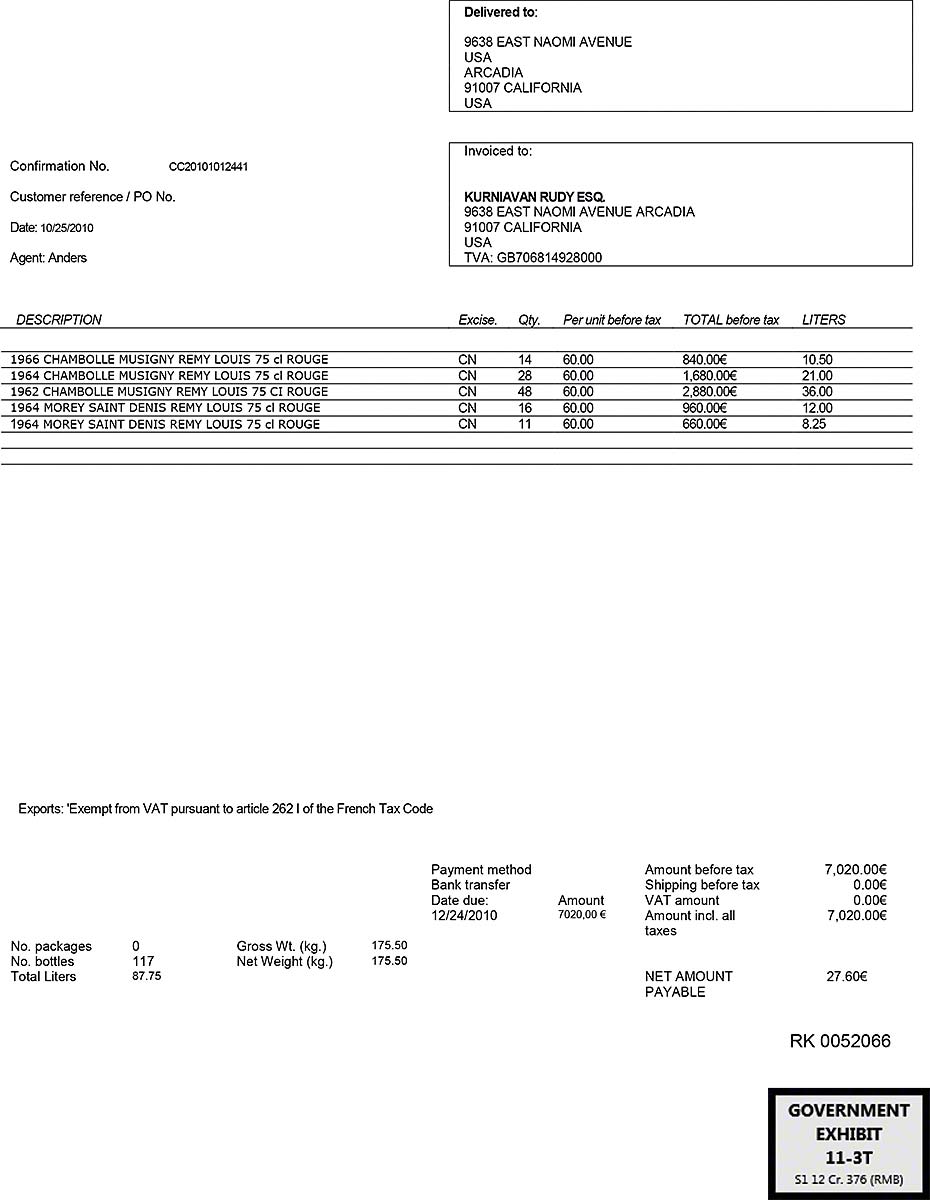

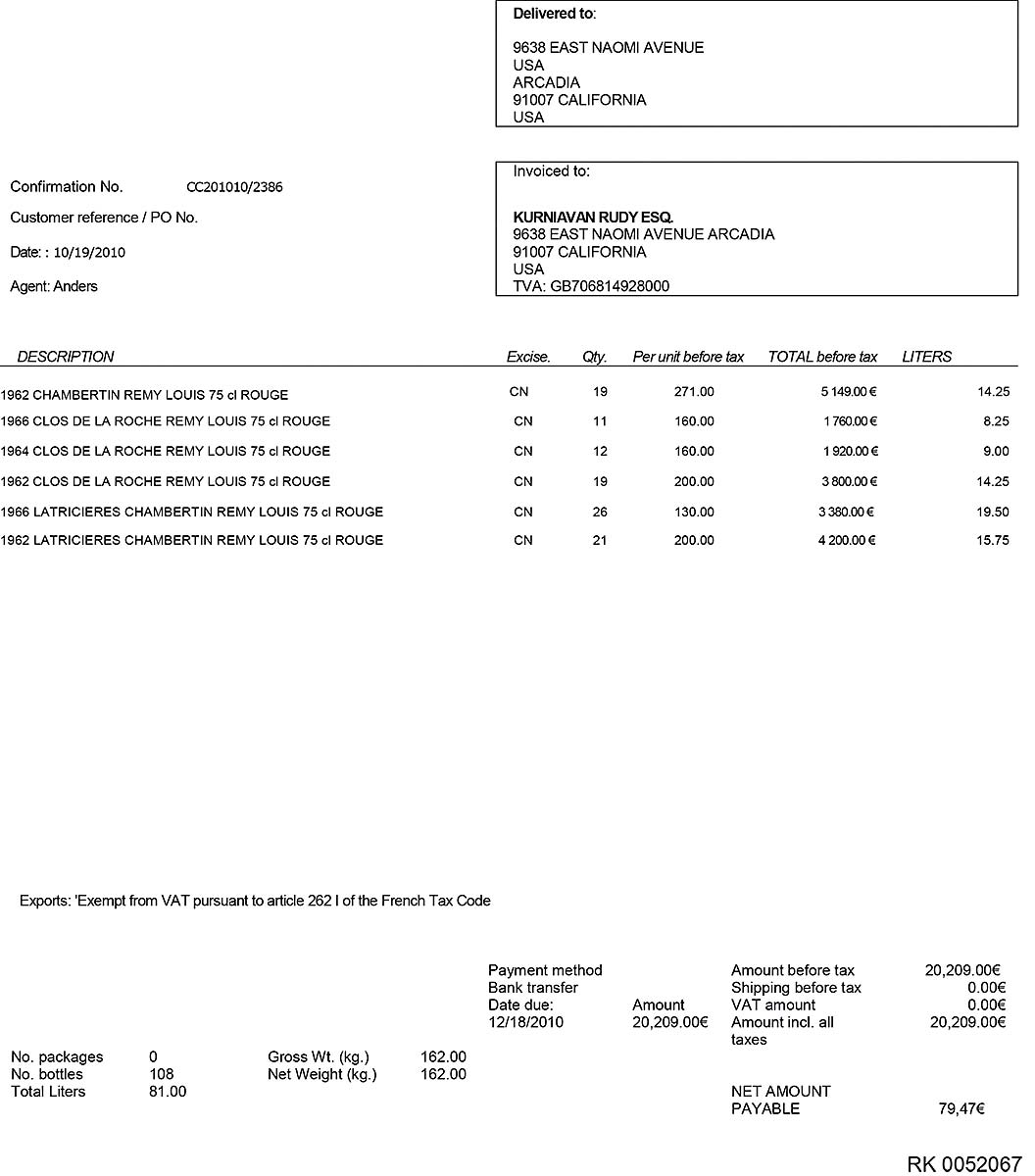

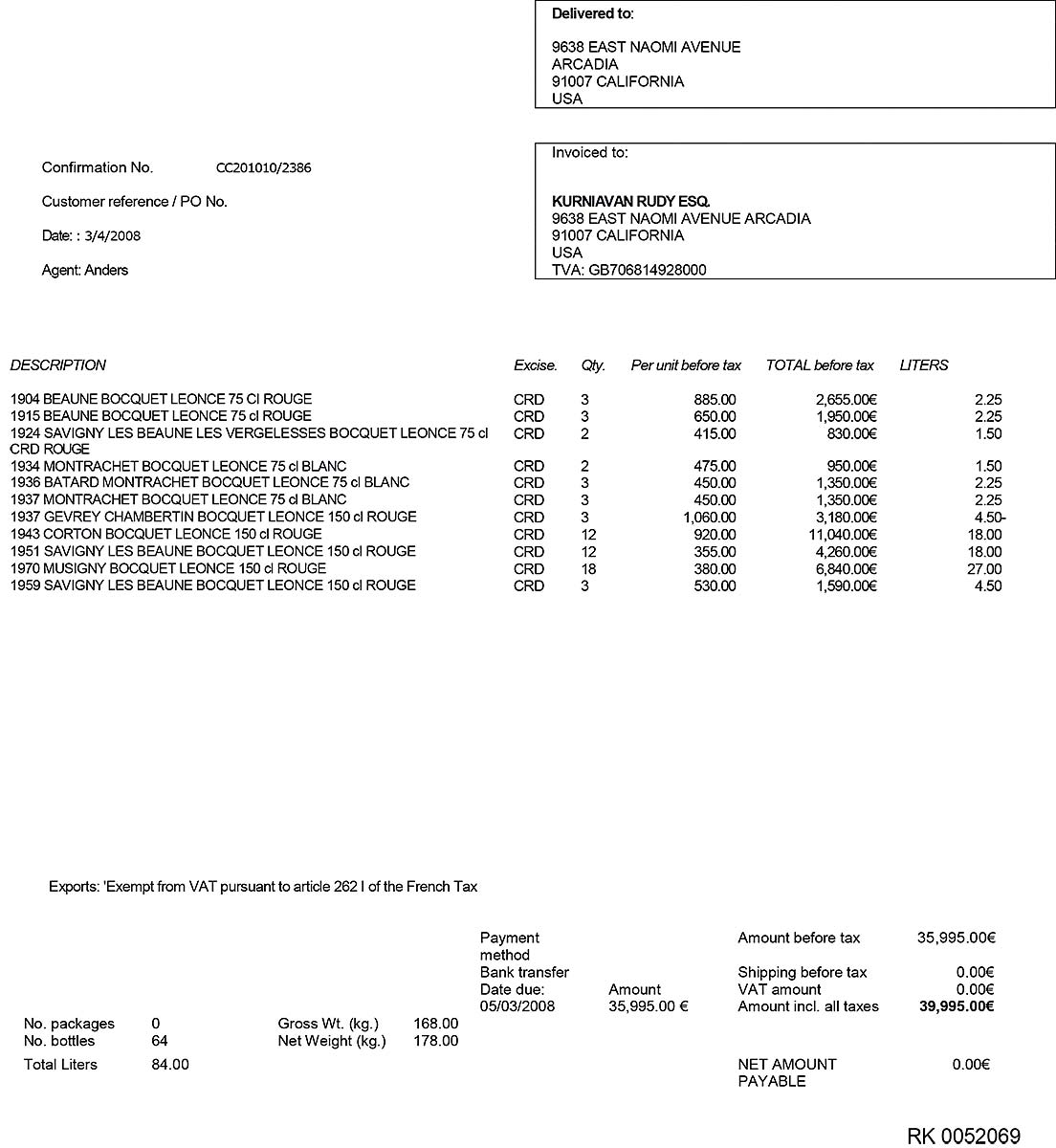

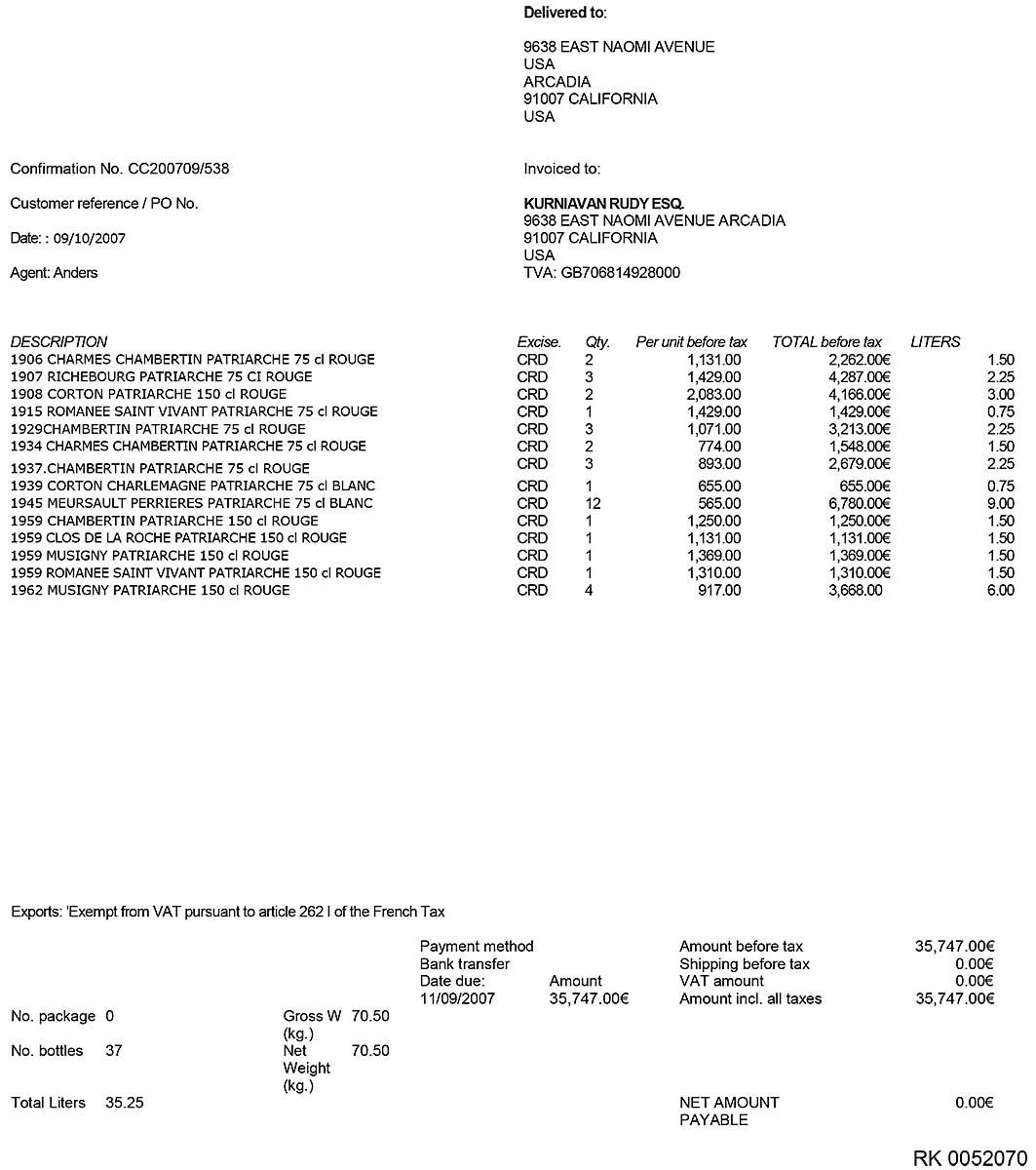

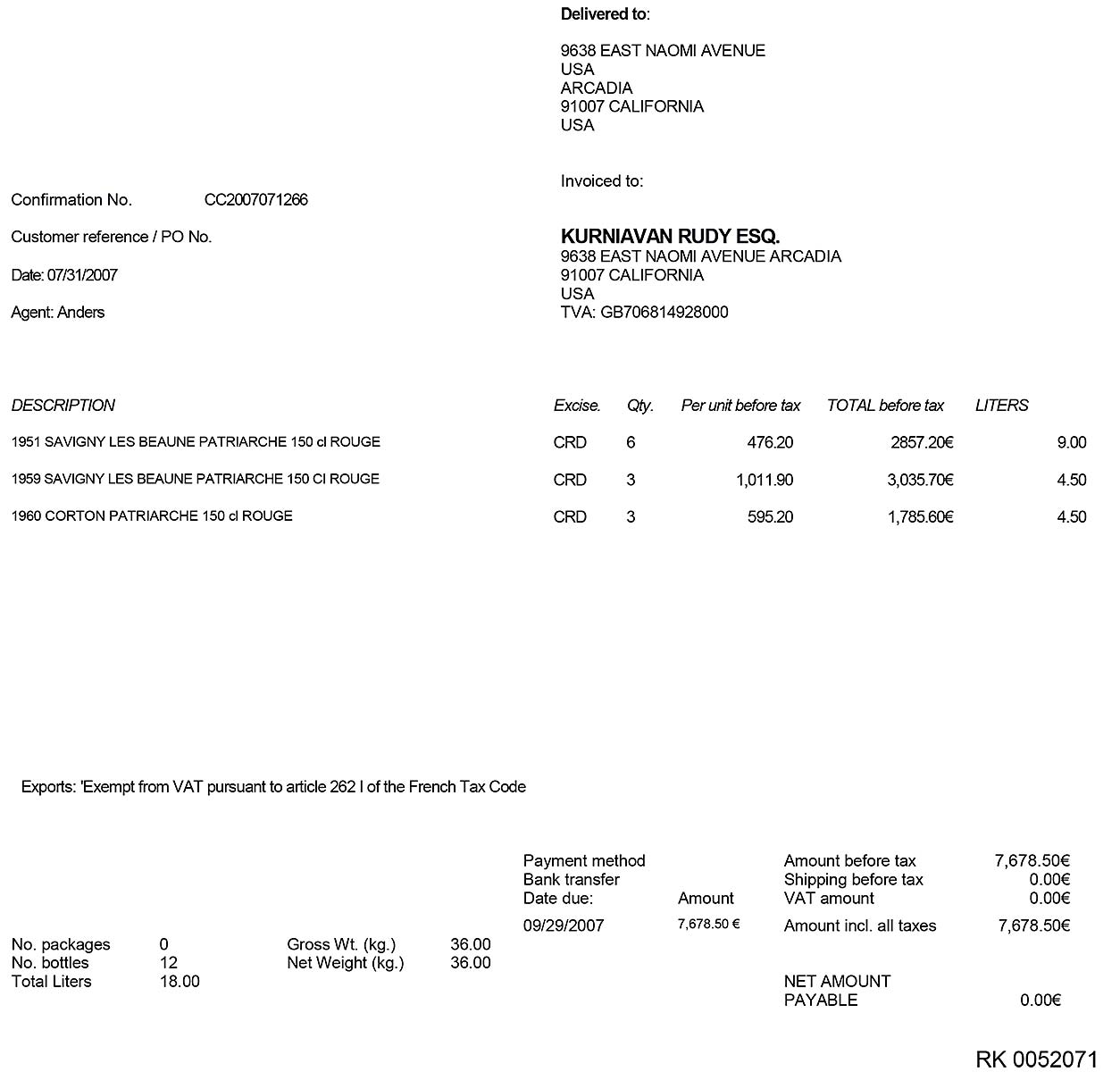

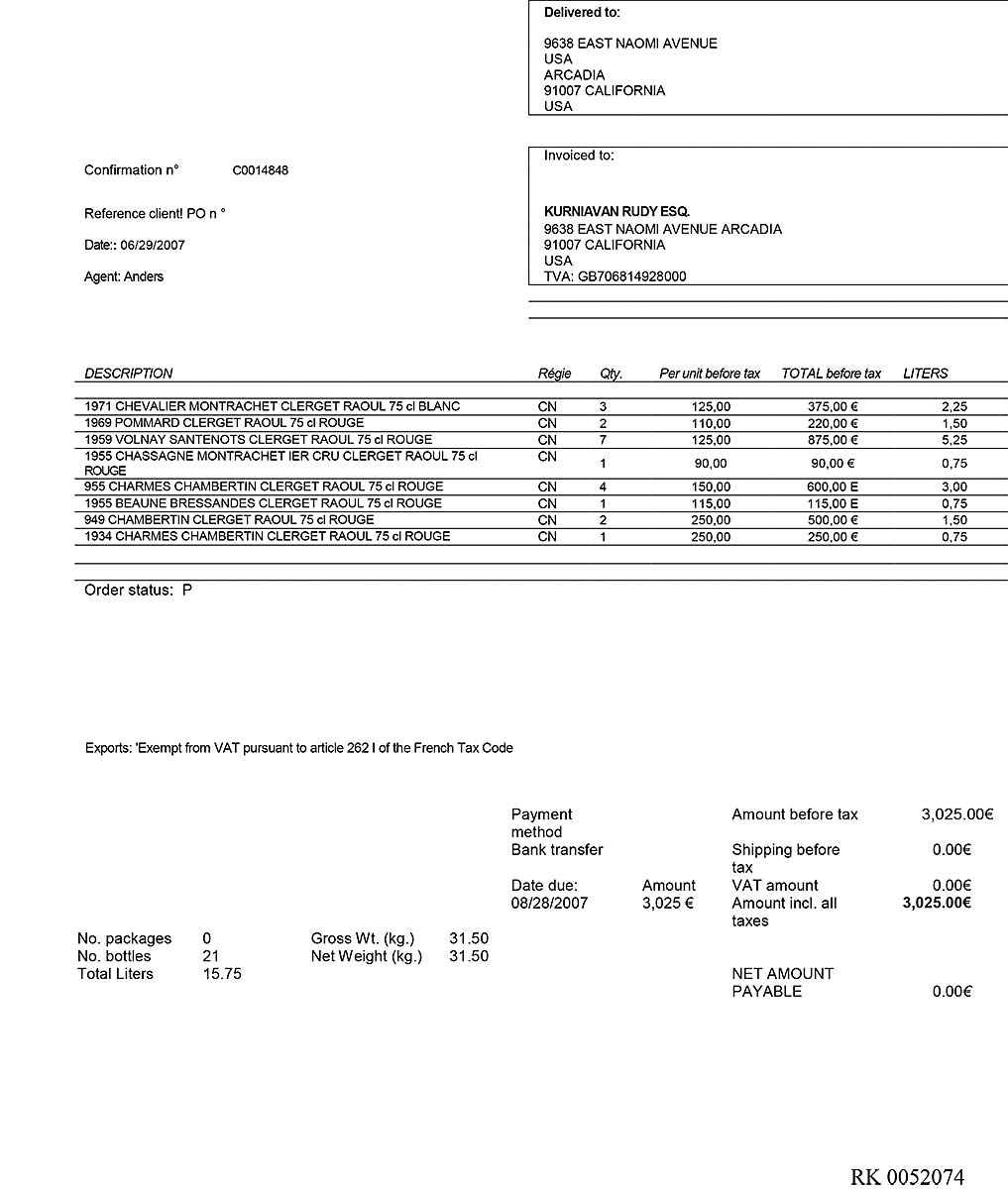

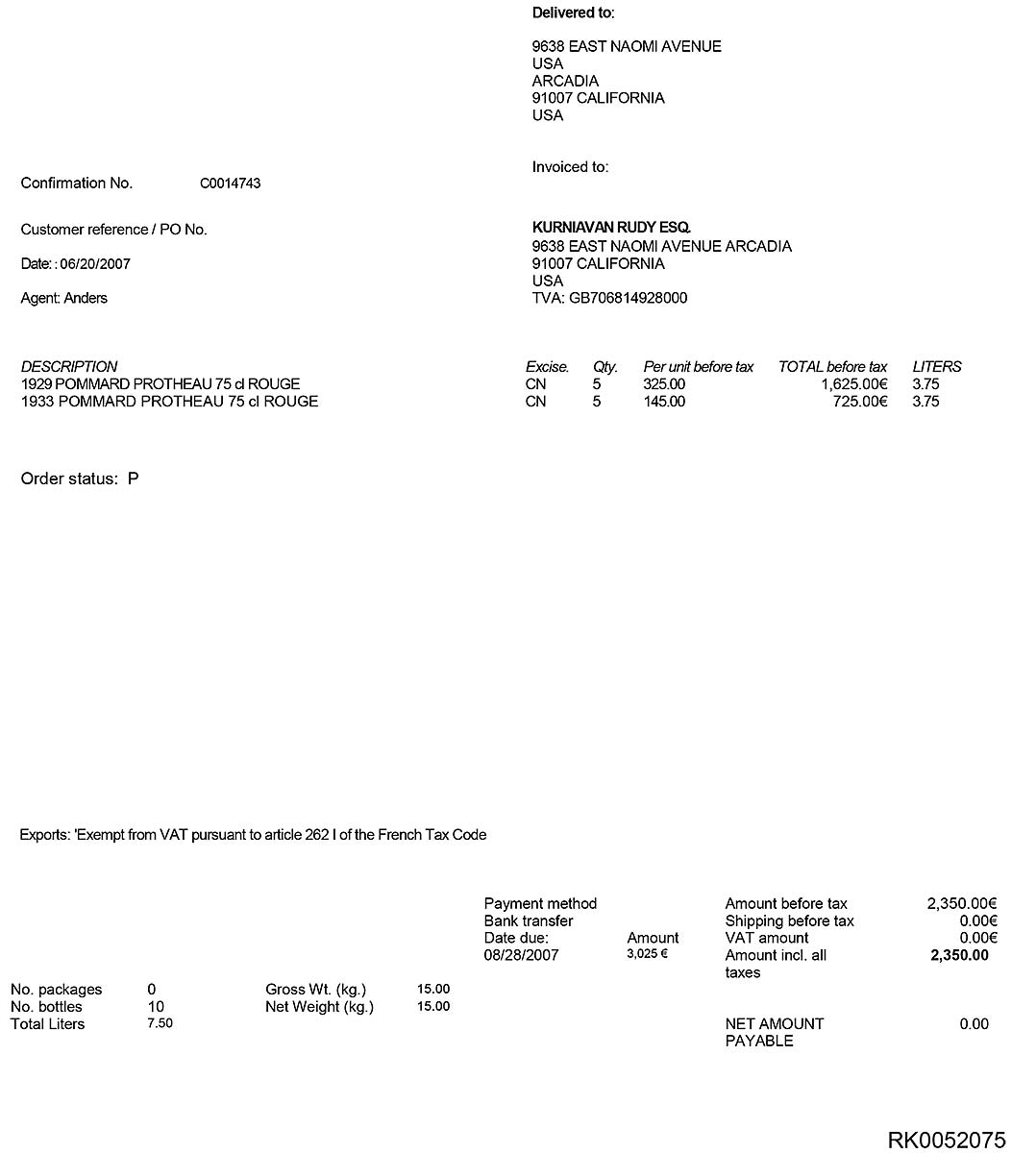

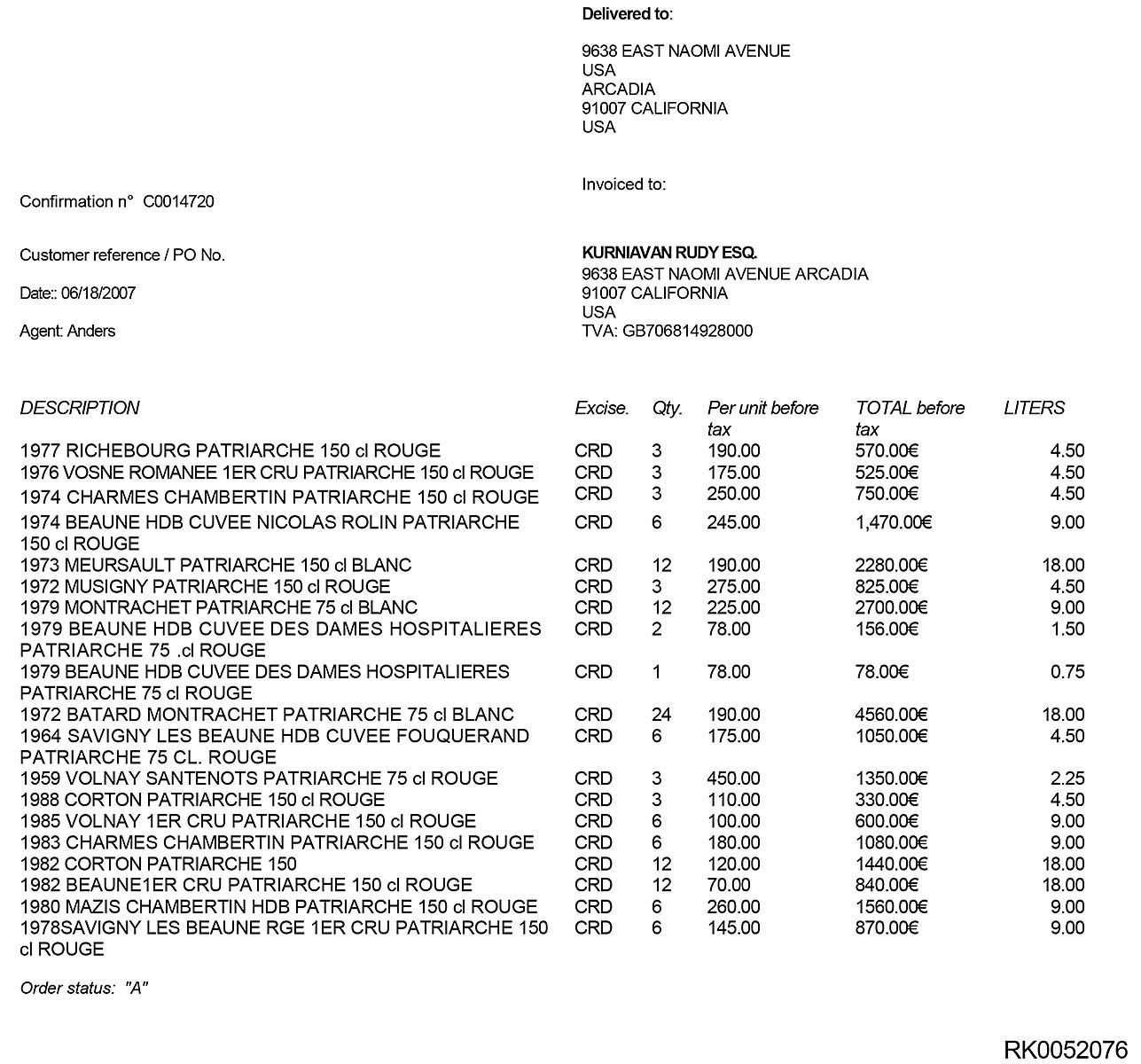

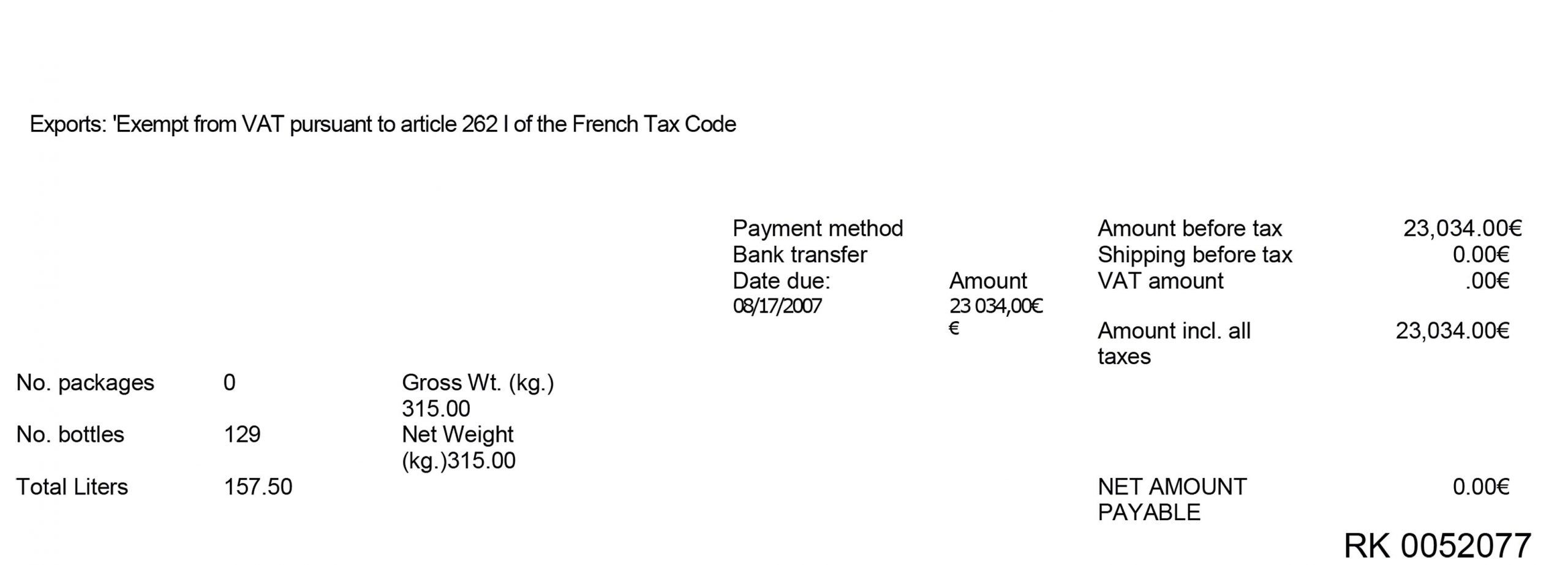

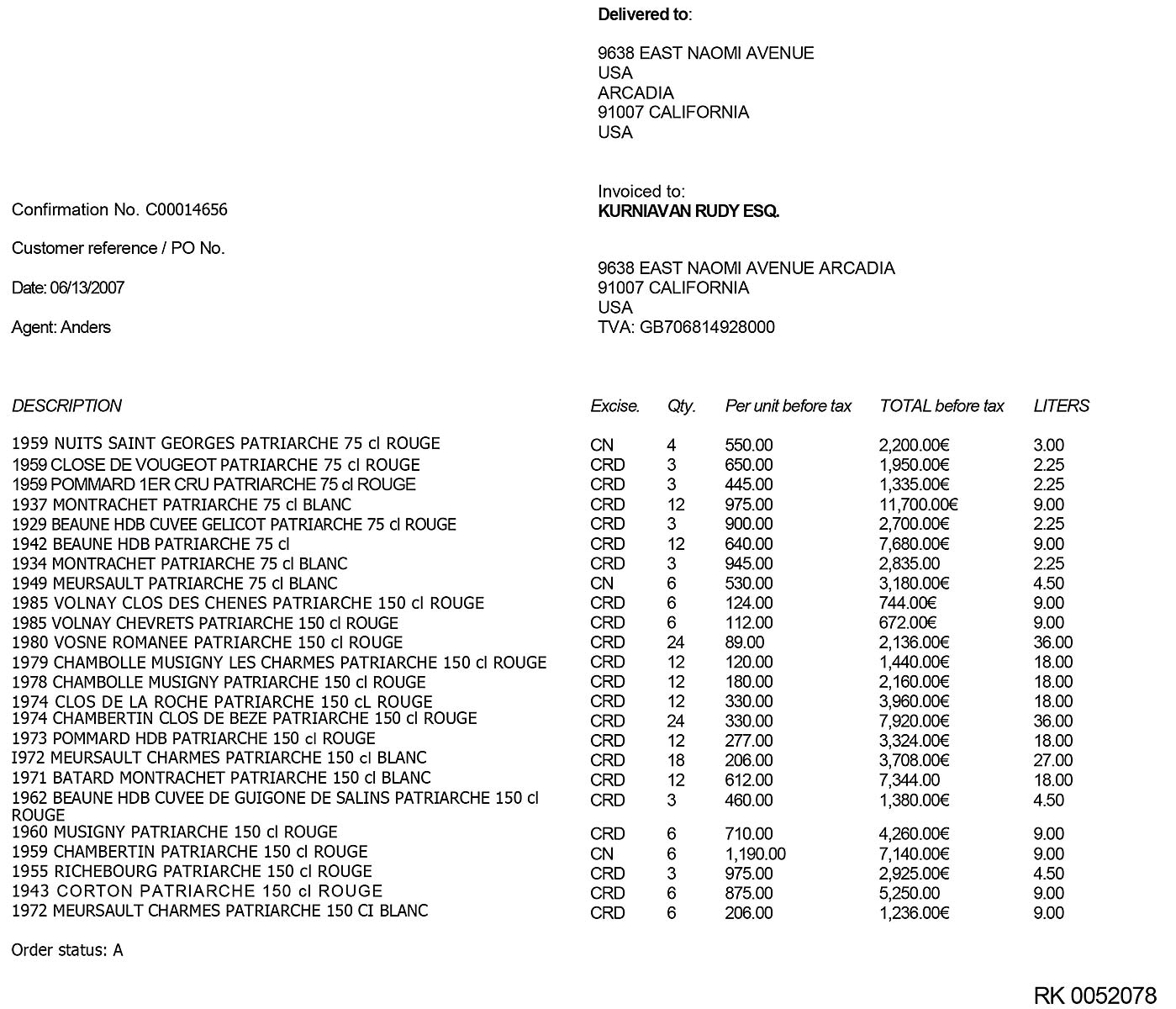

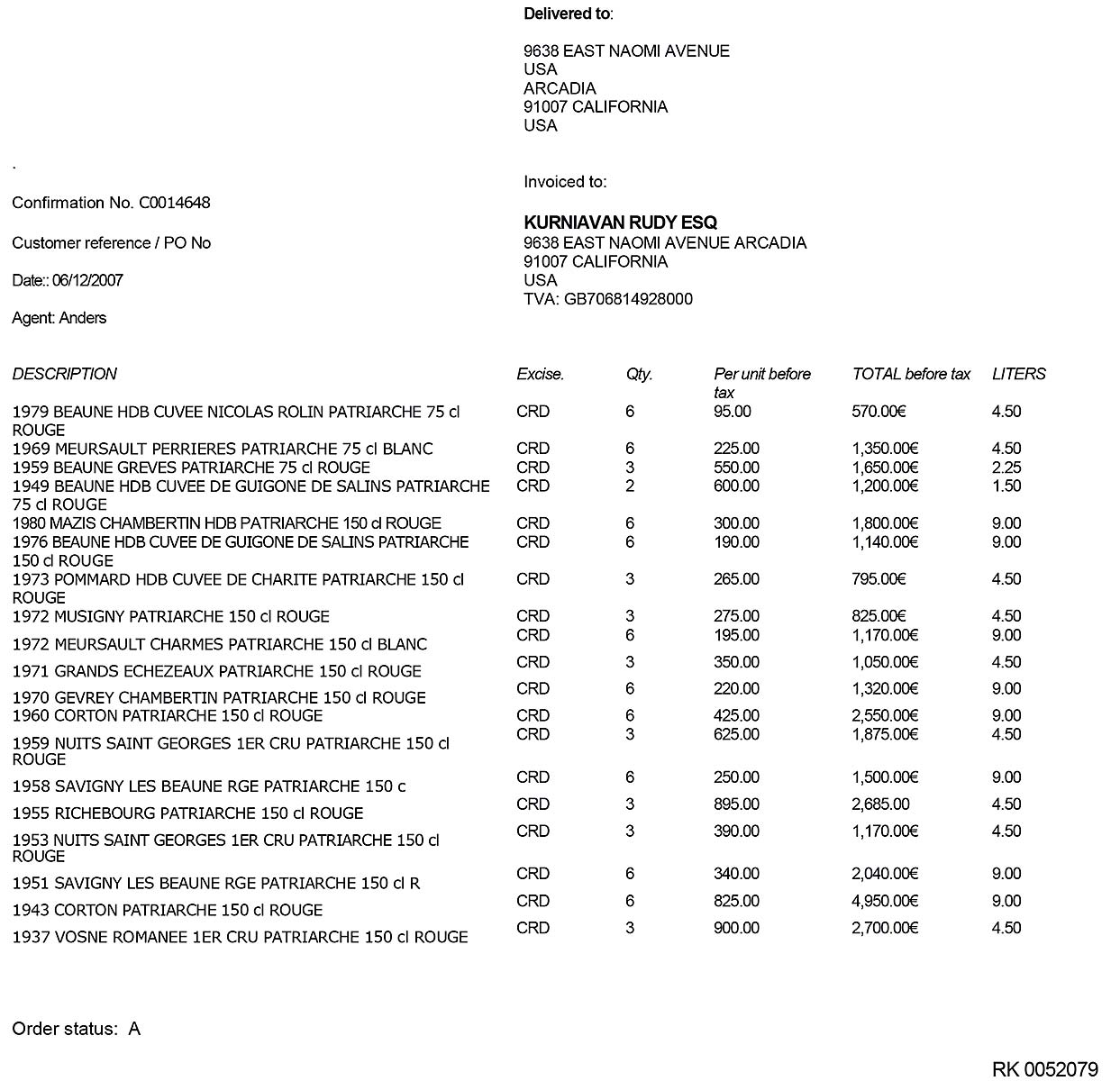

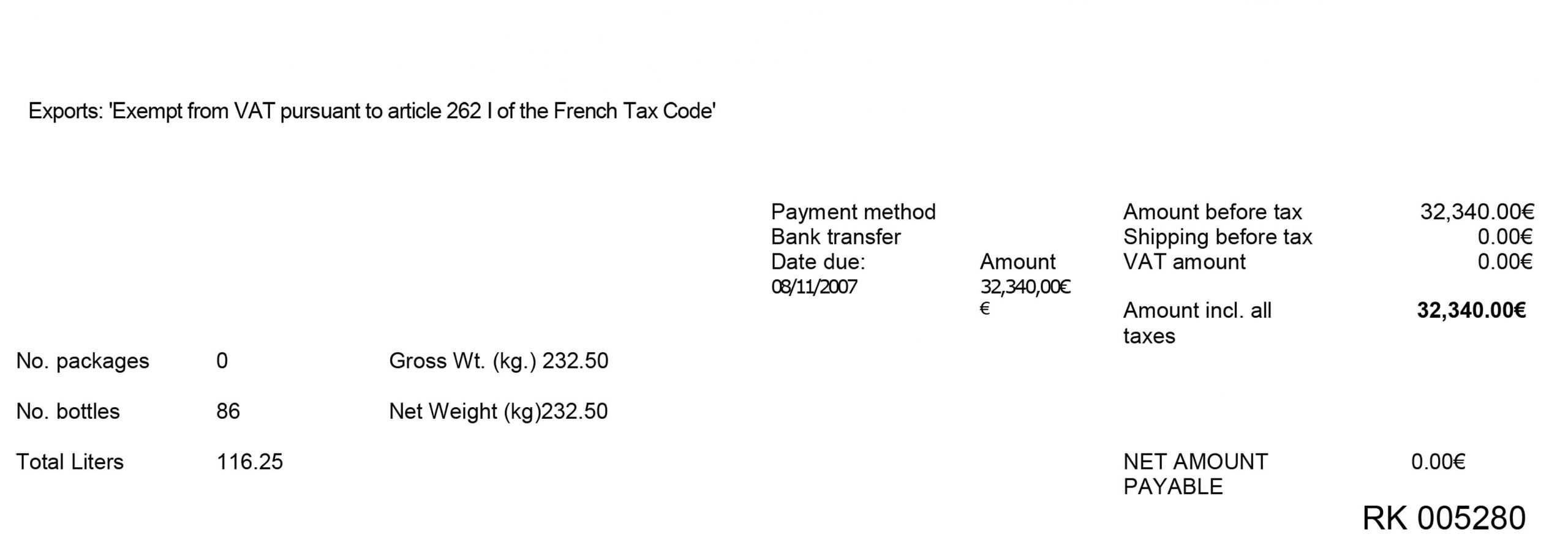

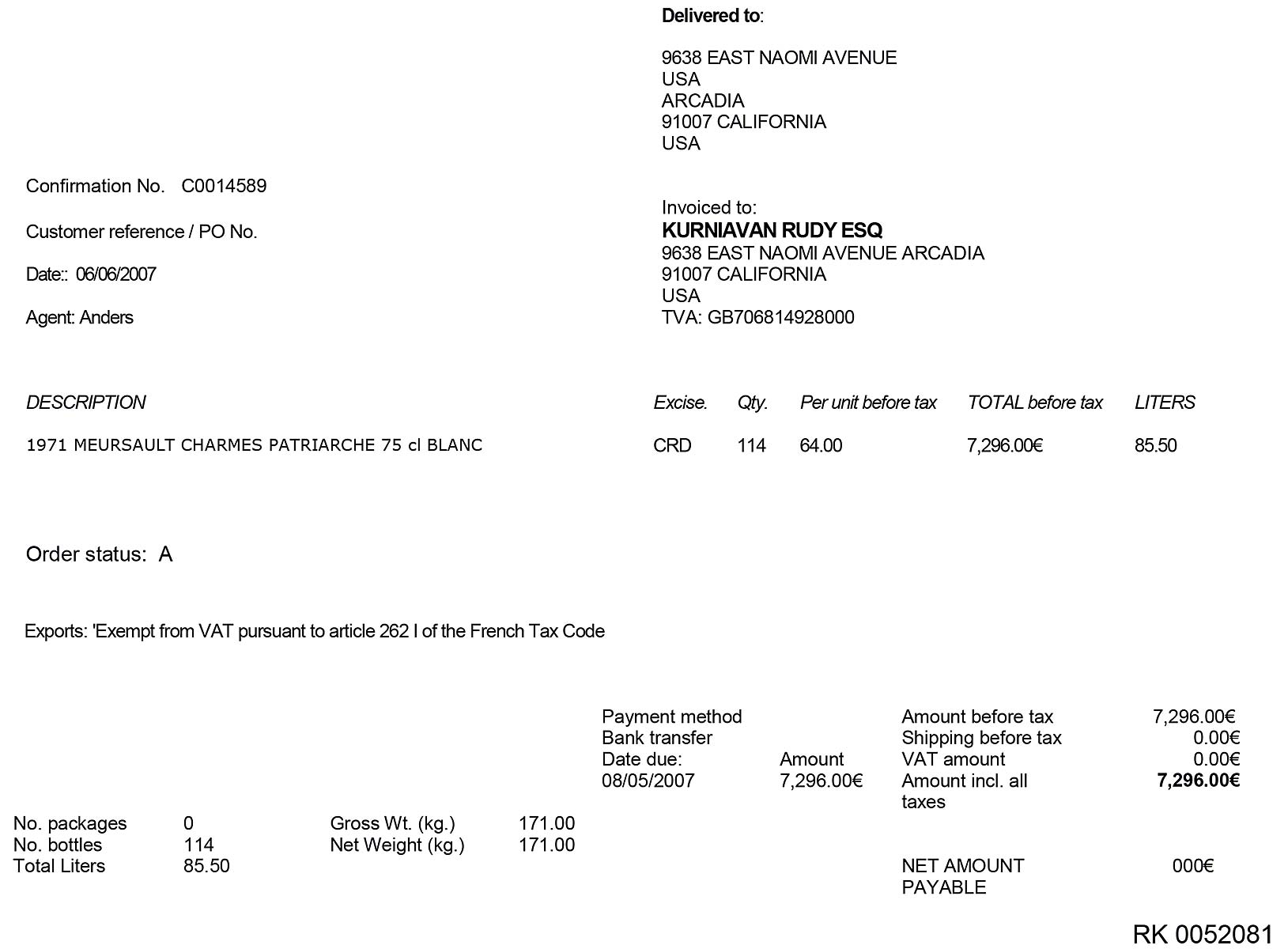

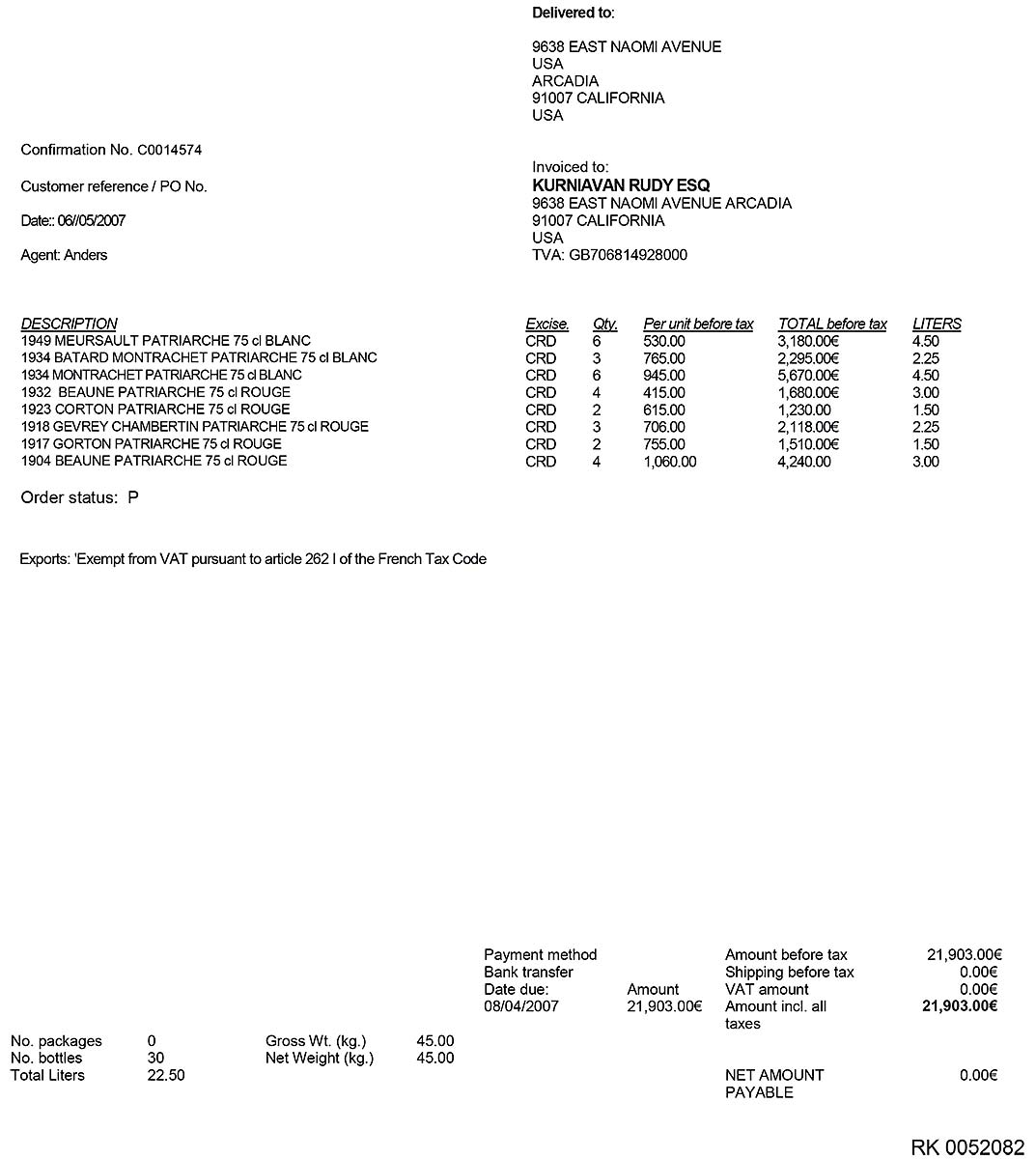

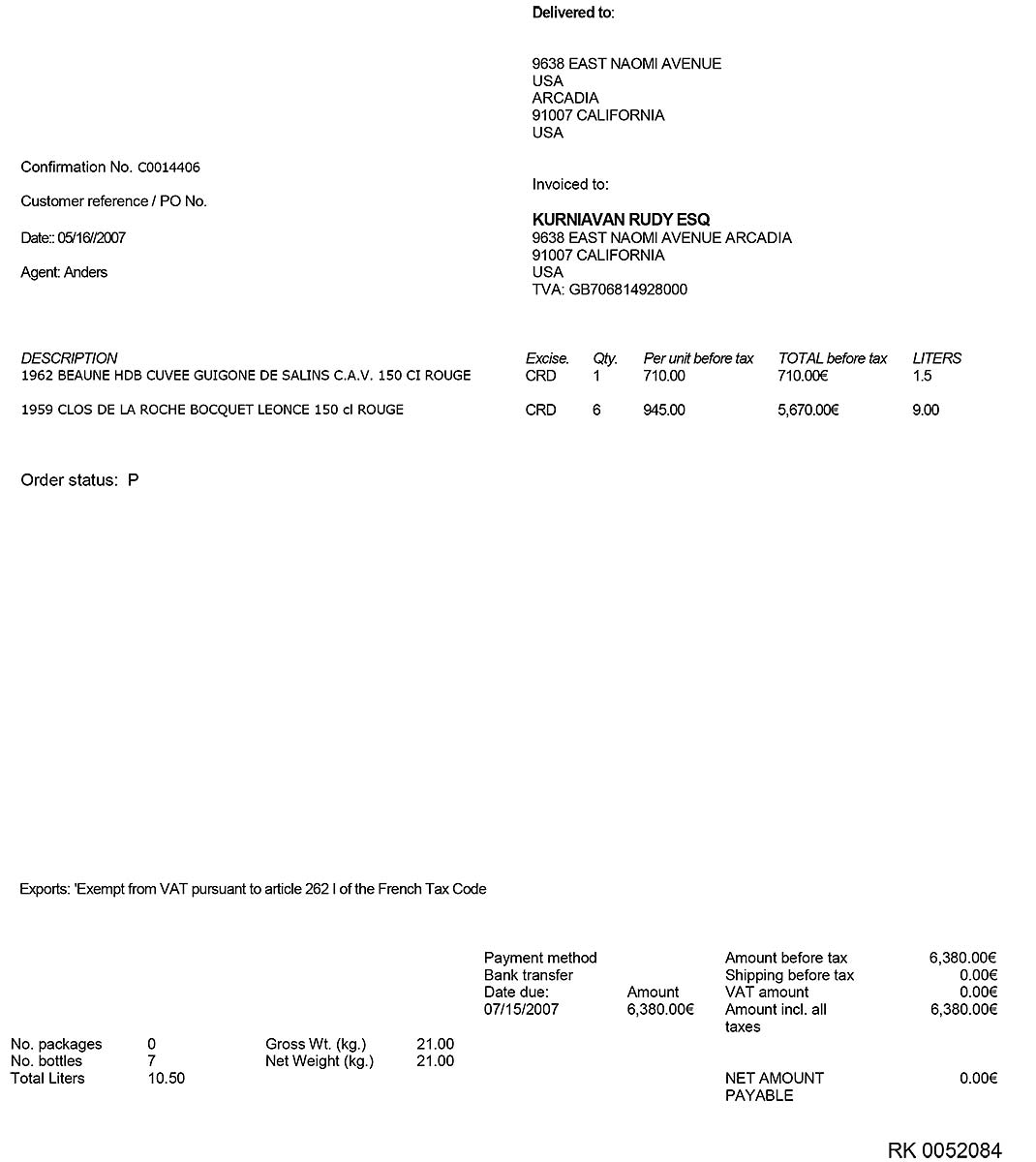

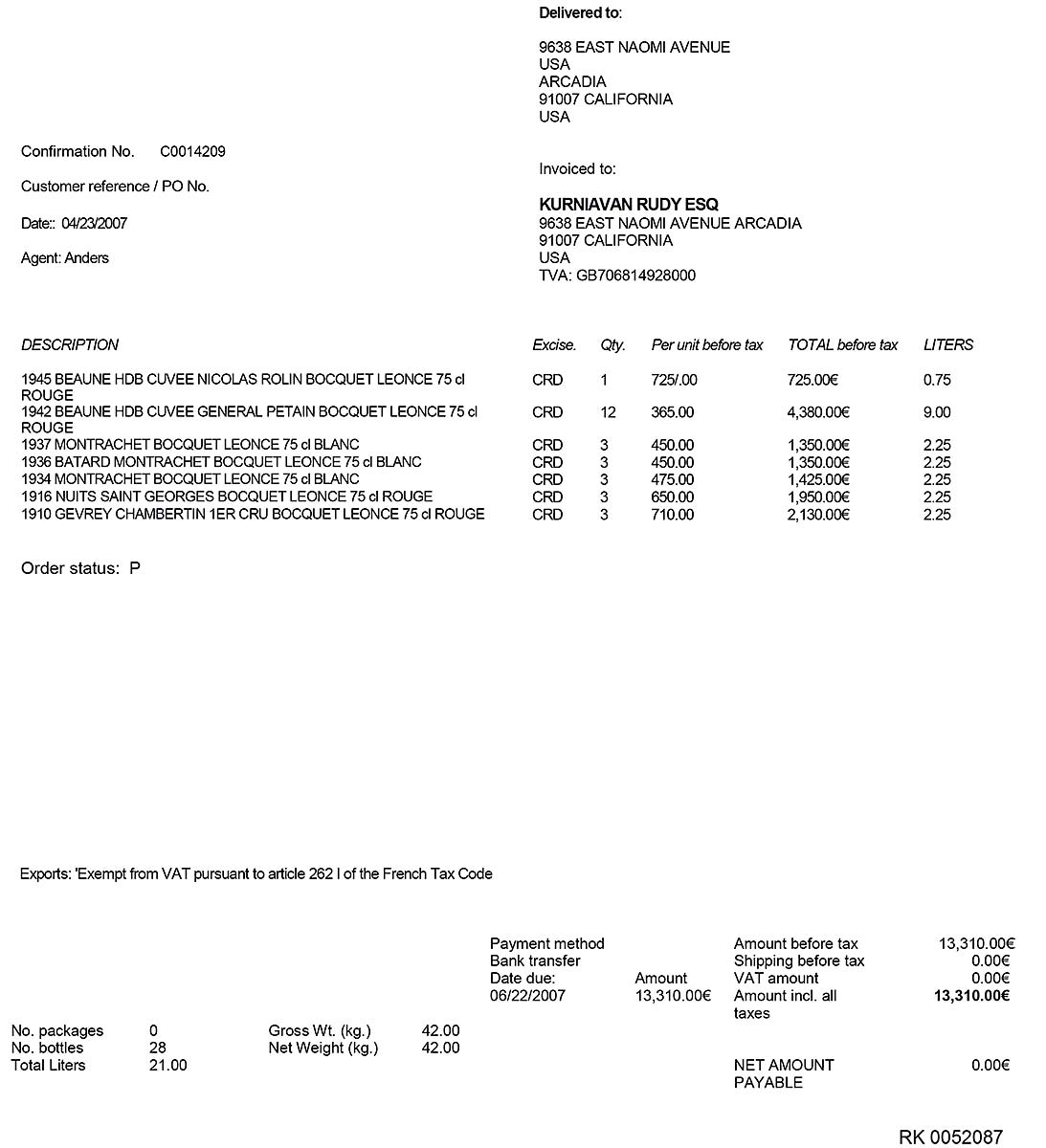

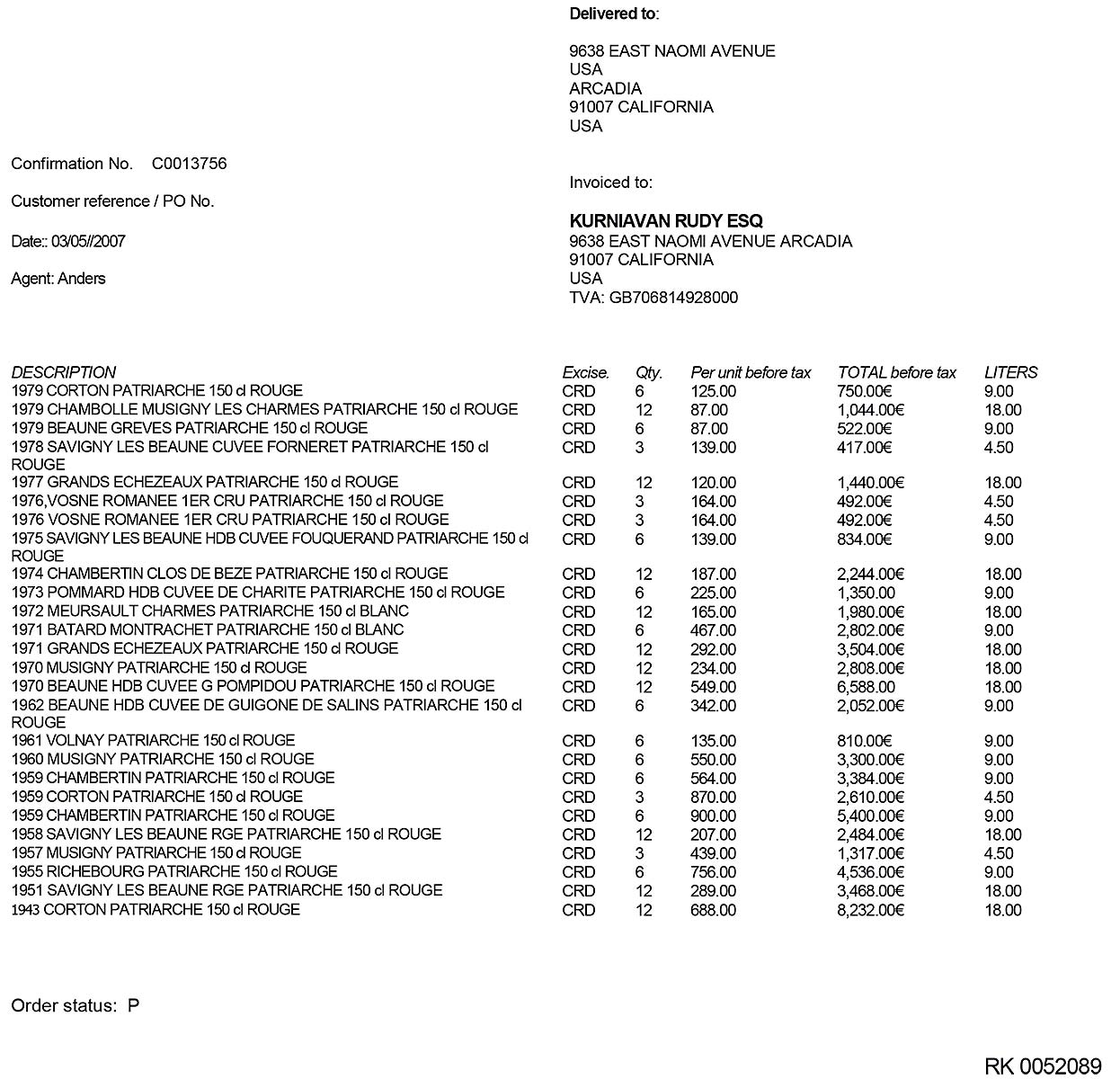

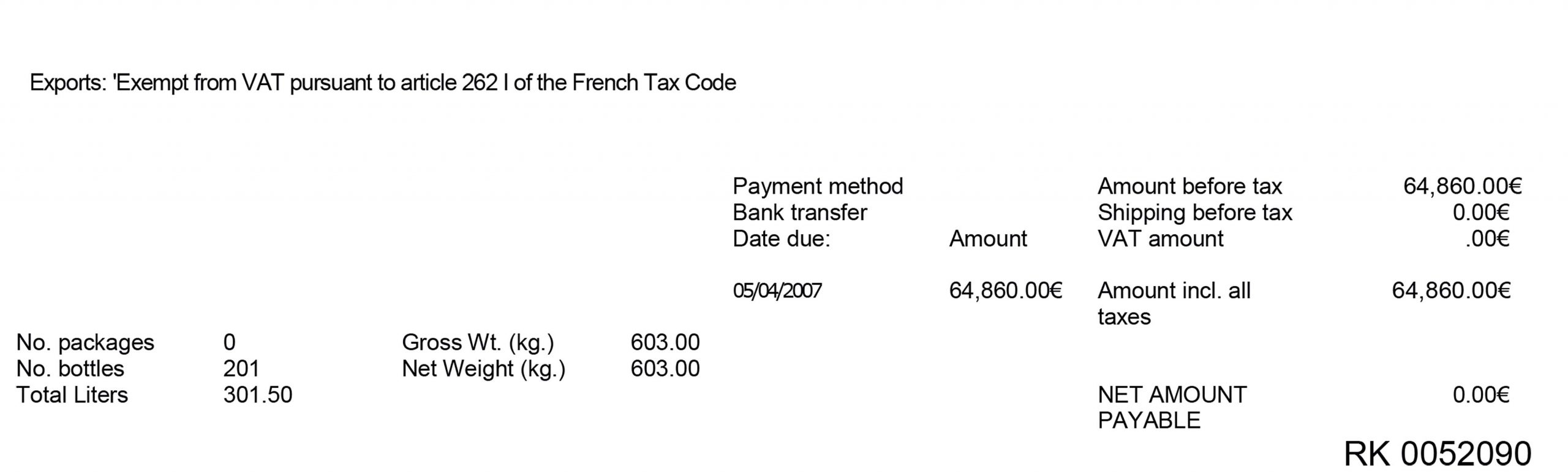

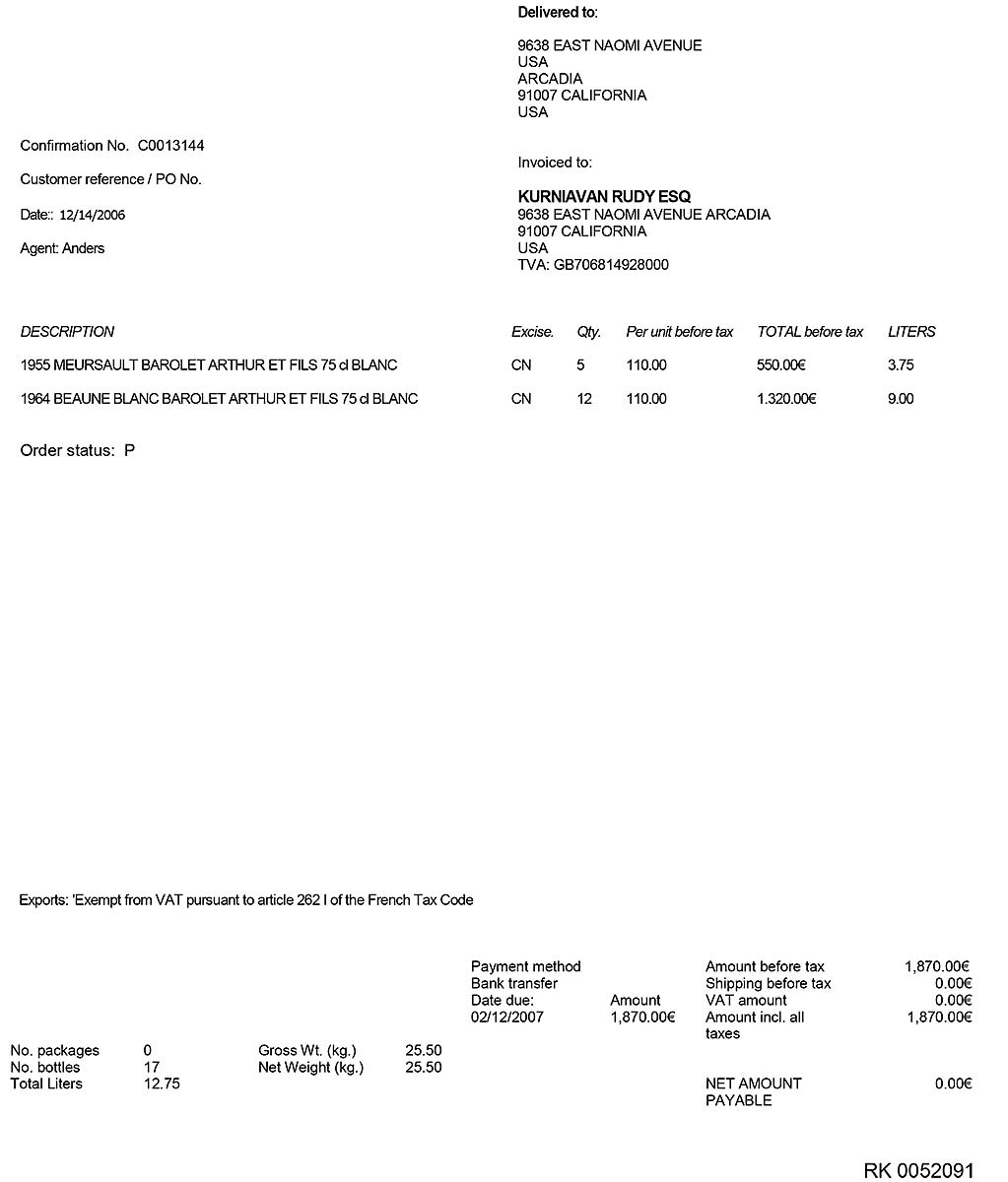

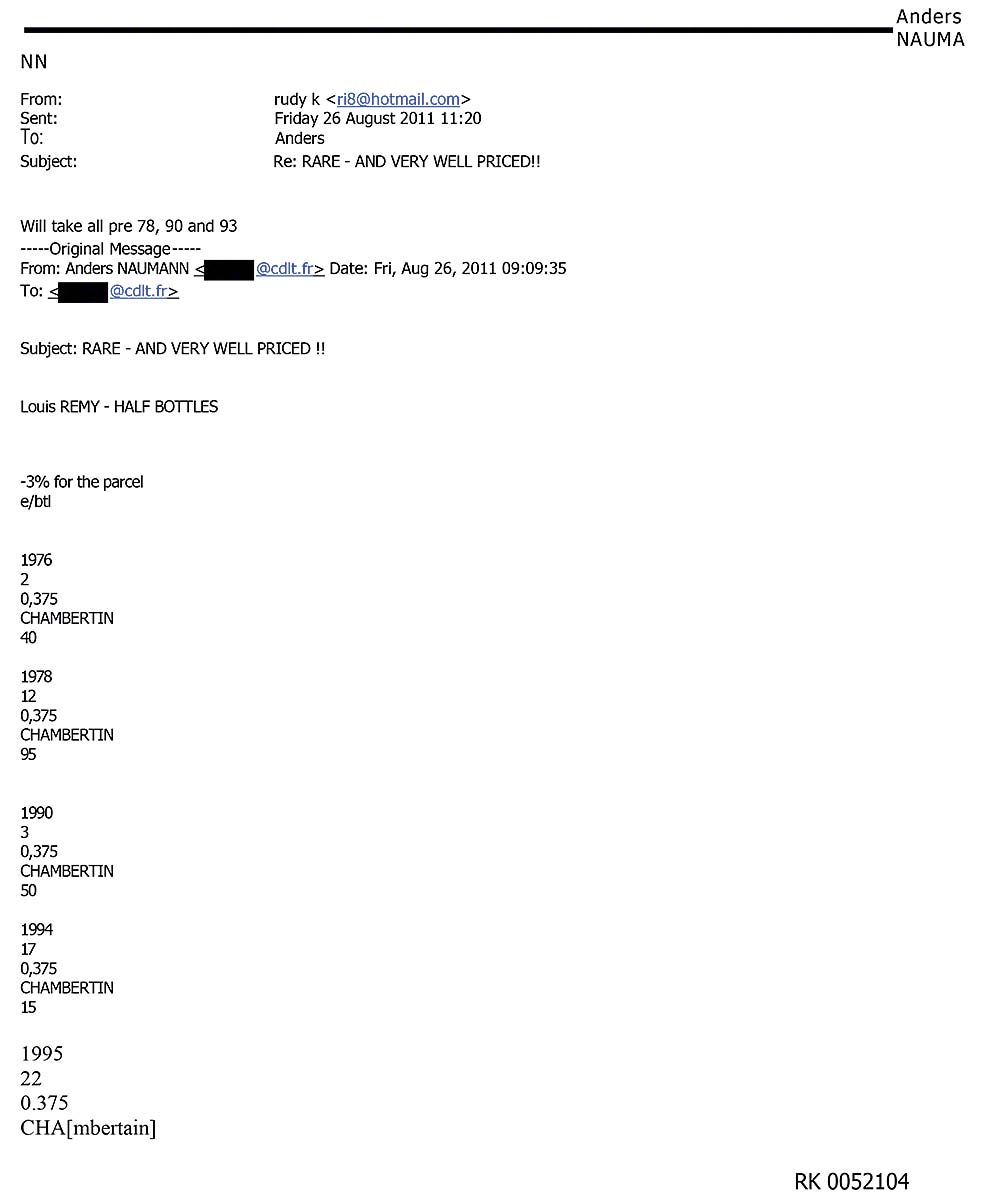

Hernandez then asked if Egan had seen records of Kurniawan purchases of Patriarche and Louis Remy wines, which Egan confirmed. He explained that Patriarche is a well-established Burgundy merchant, dating back to 1780. They owned a number of vineyards, including parts of Richebourg and Romanée-Saint Vivant, but they also produce a lot of proprietary blended wines – adequate, but nowhere near the quality or desirability of the wines in the present case. Louis Remy is similar, and both are substantially cheaper to purchase. Egan noted that none of his clients with cellars comparable to the defendants had ever shown any interest in wines such as these.

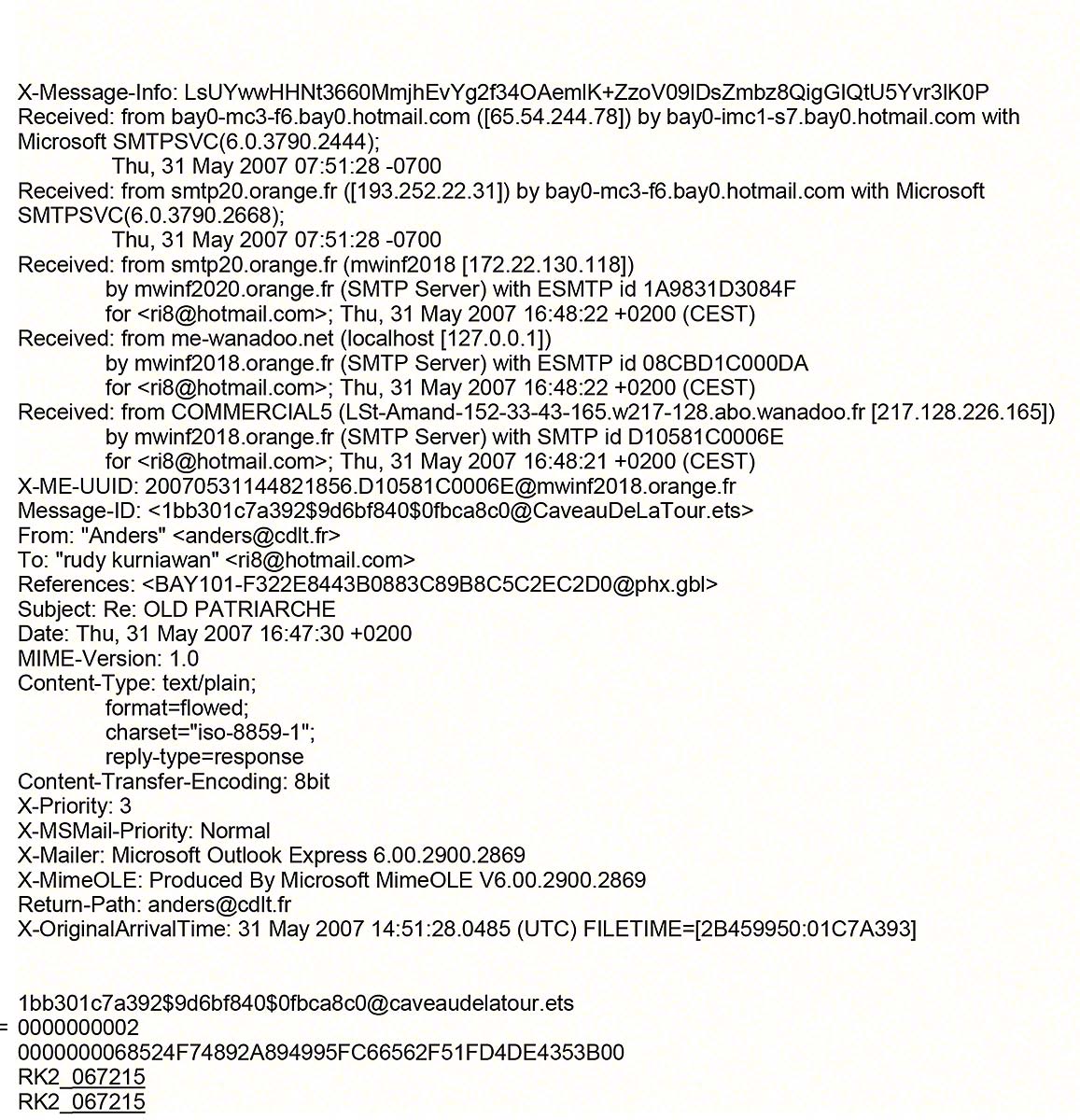

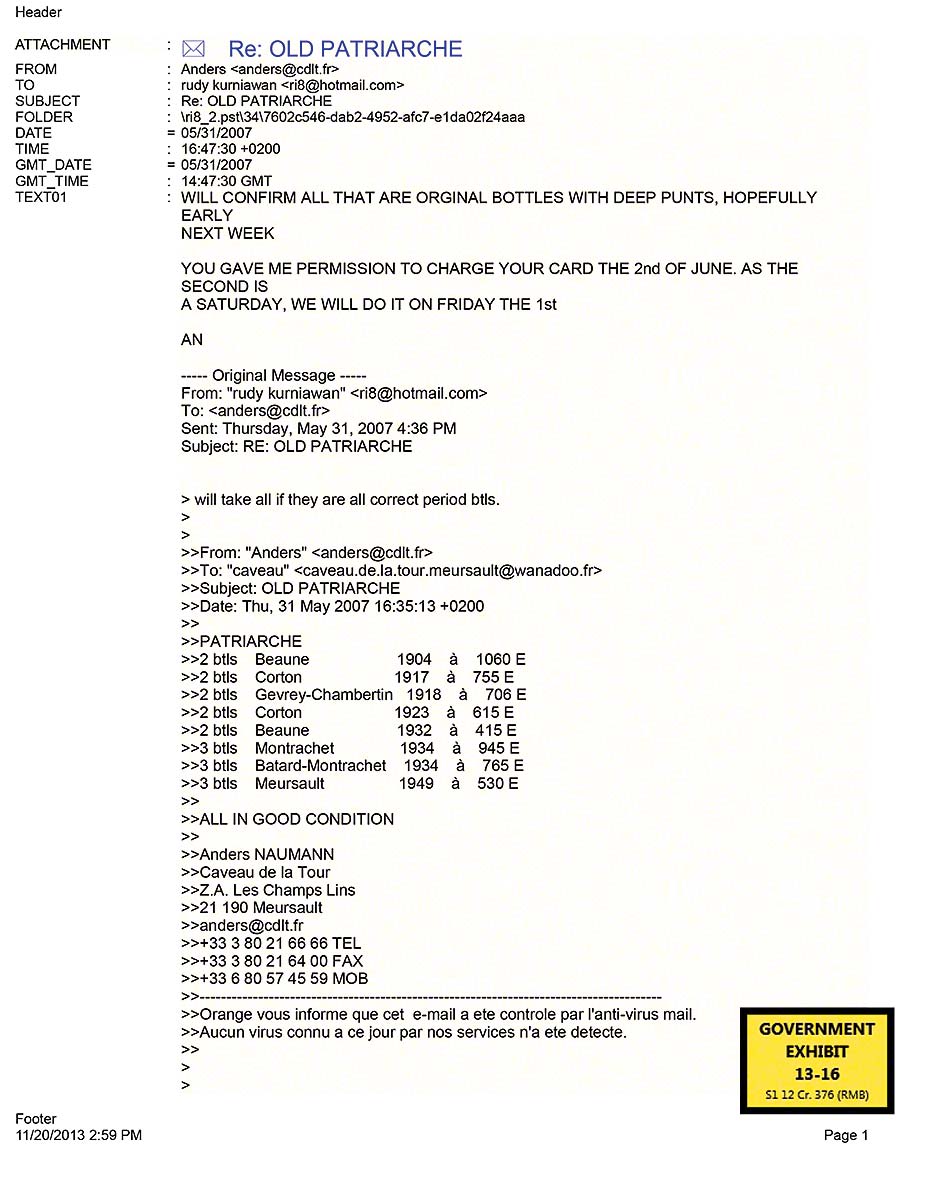

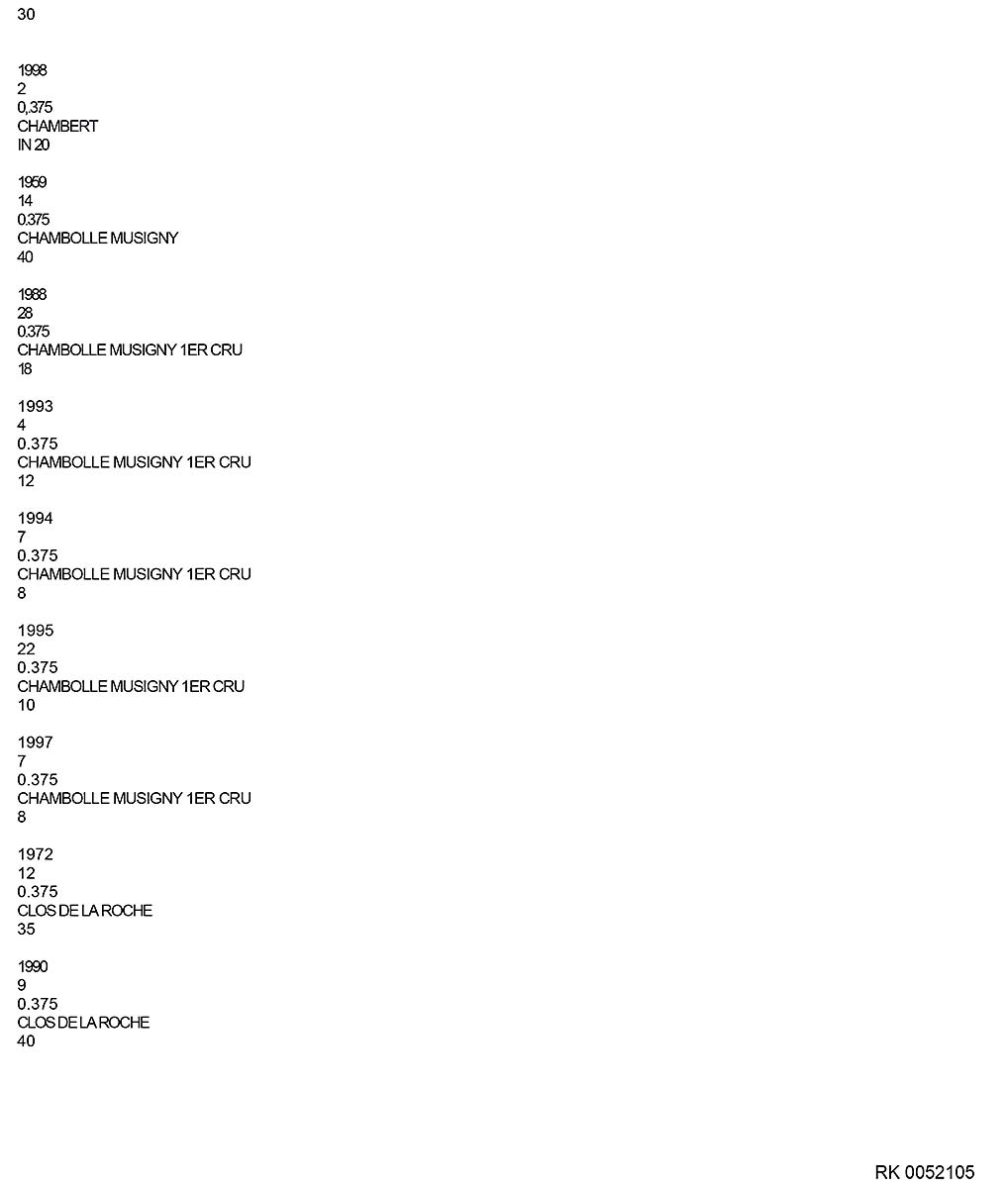

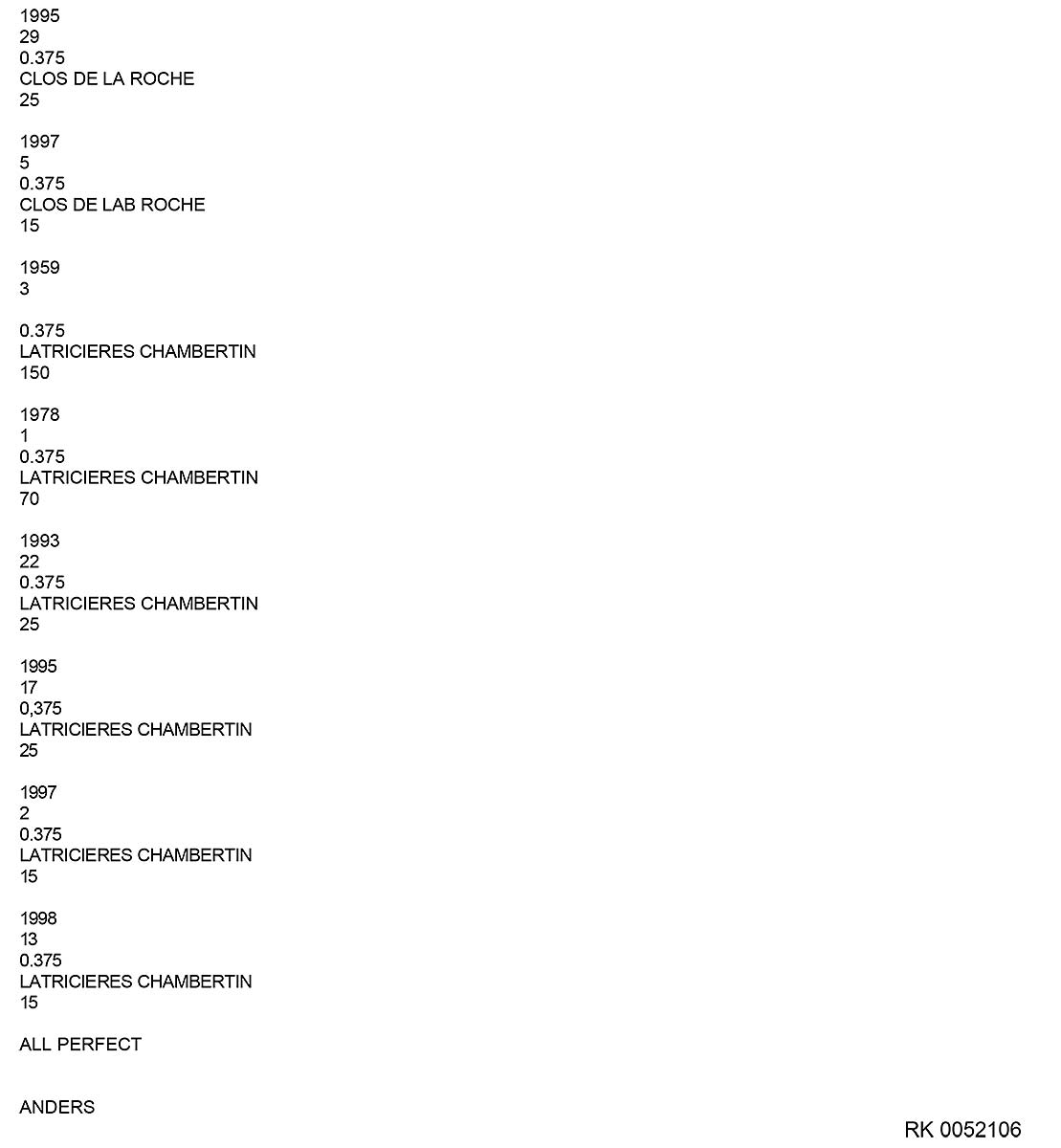

Hernandez then showed Egan Exhibit 11-3T, an invoice from broker Caveau de la Tour for the purchase of a large number of wines from Louis Remy, including 14 bottles of 1966 Chambolle Musigny and a number of other village level Burgundy wines from the 60s, all at €60/bottle. The exhibit also included an invoice for Patriarche wines, including a magnum of 1977 Richebourg Patriarche for €190, and some 1979 Beaune wines, and more from 1974. Egan noted that these were at best very ordinary vintages in Burgundy. There were also 114 bottles of 1971 Meursault Charmes from Patriarche for €64/bottle; Egan commented that in his opinion, this was pretty old for a white Burgundy from this producer. It was, he thought, a lot of bottles of wine that would not be any good any more, and he has never known any high-end collectors to purchase such wines in this quantity. In total, 904 bottles were purchased.

Egan then examined a magnum of 1908 Patriarche Corton, that had been recorked and recapsuled by Patriarche. It is a very old bottle, hand blown, with a very deep punt, typical of that time. Compared with, for example, the more modern Californian bottles, it has no seam, and, being hand blown, it is less even. It would rock if you put it on the table. Around the neck, it has an enlarged collar, which is to reinforce the hand-blown bottles. They are very different from modern bottles.

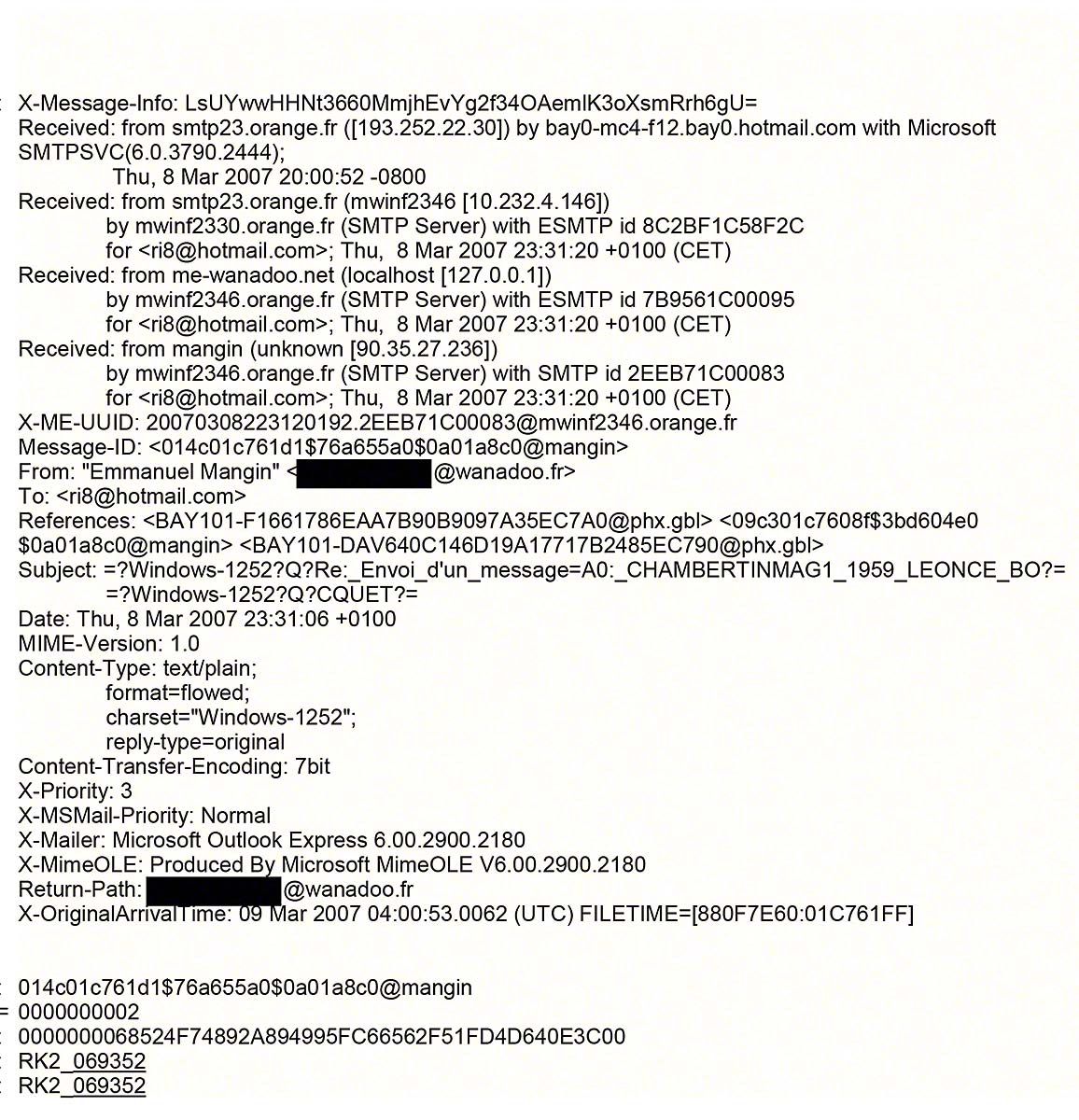

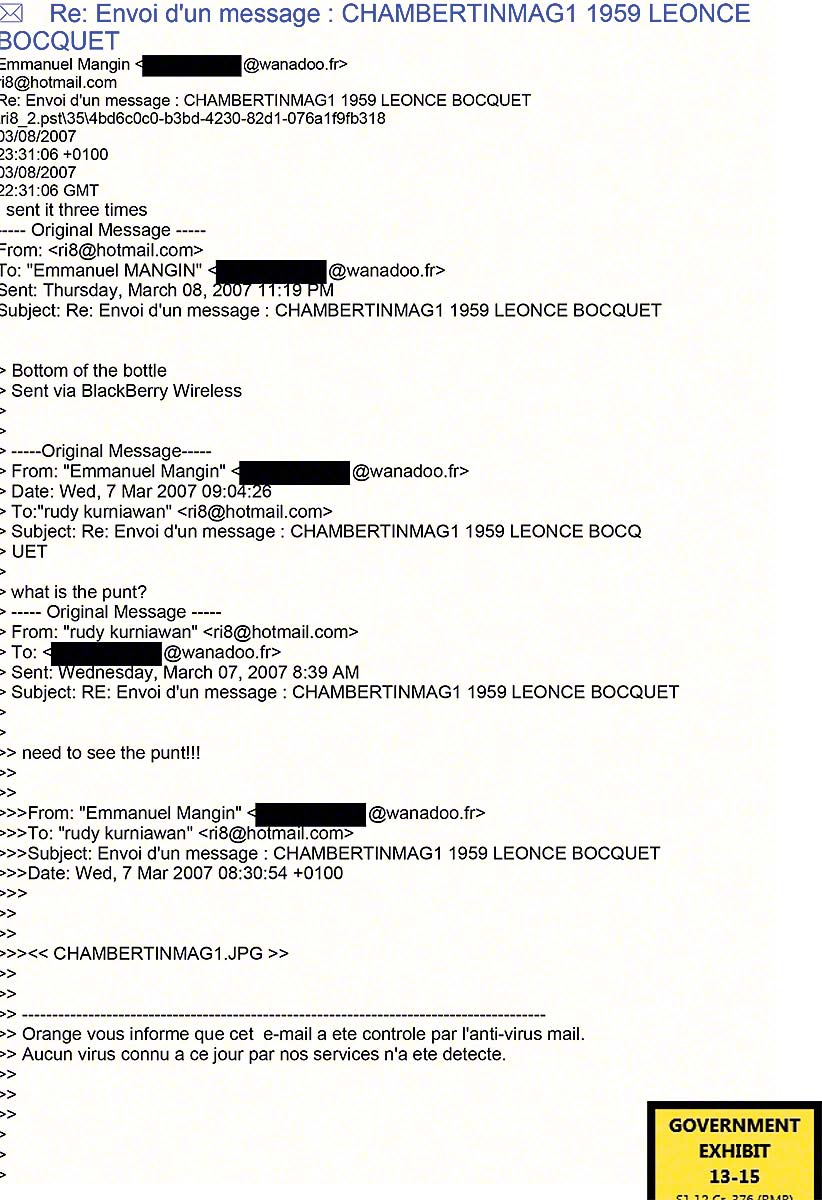

Hernandez then directed Egan’s attention to three emails, Government Exhibits 13-15, 13-16 and 3-29.

In these exhibits, Kurniawan agreed to take all the wines as long as these were in bottles from the correct period. In one, for a 1959 Leonce Bocquet Chambertin magnum, he emails back that he needs to see the punt (with three exclamation marks).

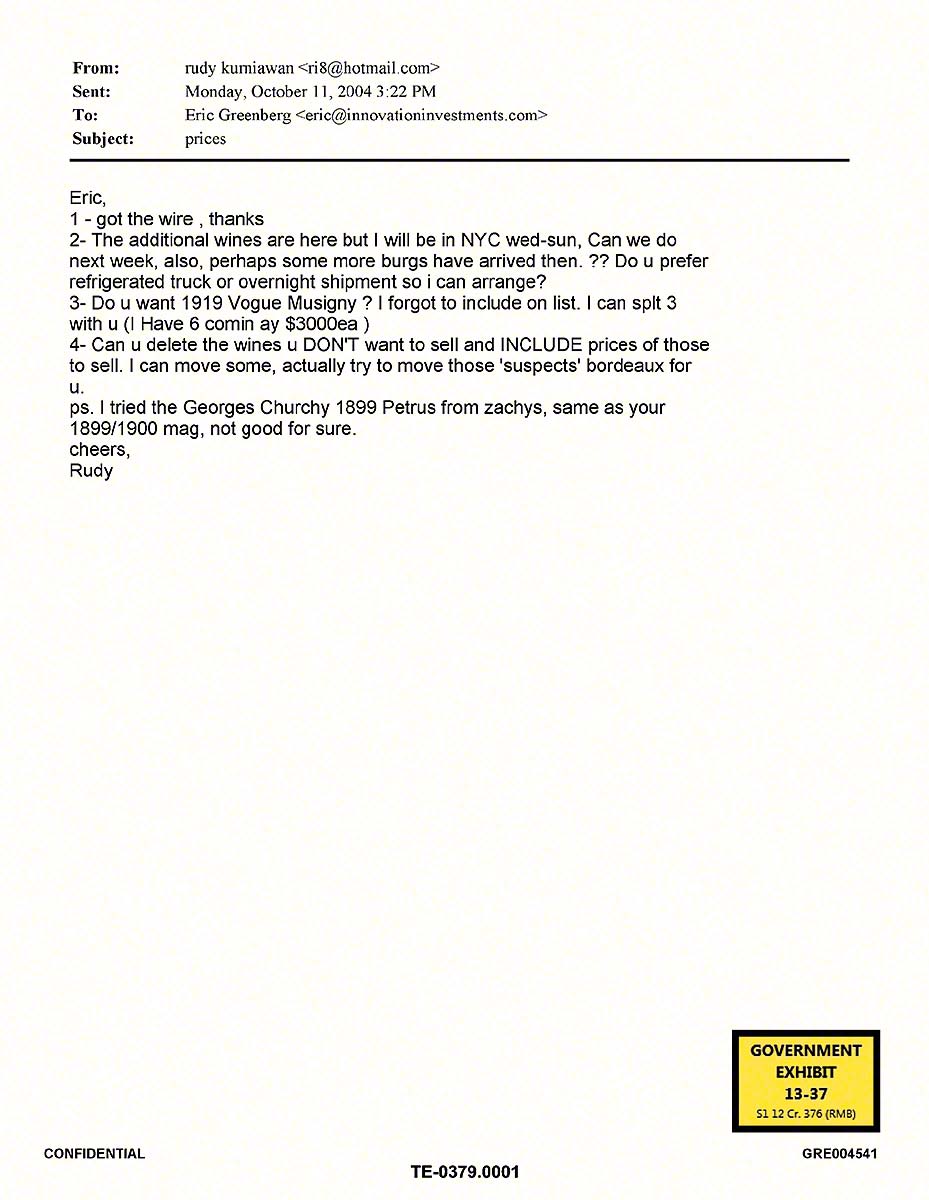

13-37 RK to EG SUSPECTS Bordeaux email

Hernandez then produced an email exchange dated 11 October 2004 between Kurniawan and Eric Greenberg, and asked Egan if he knew who Greenberg is. Egan replied that he did indeed, and added, “He is a wine collector and has also been shown in court to have sold fraudulent wines.” The email indicates that Kurniawan was selling wine to Greenberg.

In the email, Kurniawan writes “I can move some, actually try to move those ‘suspects’ Bordeaux for you” which in the context Egan said obviously meant doubtful Bordeaux wines.

Hernandez then asked Egan to step down to the exhibit table again. The witness testified that he had examined the bottles that were at issue in the trial, and that the government alleges are counterfeit. Hernandez then showed him some bottles and asked him, if he had an opinion on authenticity for each bottle, to express it to the jury.

The first wines were purchased by Bill Koch. To summarise:

- Petrus 1947 double magnum: Counterfeit

- Label is photocopied

- Capsule is not from the 1940s, but more likely from the 1960s

- Cork branding is not well applied, and it’s too short for a real cork from that era from this chateau

- Pair of bottles of Romanée-Conti 1934: Counterfeit

- Both labels are photocopies

- Corners of labels are hand cut; real labels would be printed as a rounded rectangle

- Old wax along the neck, but the wax at the top is not the same, being softer and newer, and there are signs of the old wax being removed.

- There is sediment, which implies it is old wine in the bottle.

- The fill level is too high for the age of the bottles.

- Pair of magnums of Romanée-Conti 1962: Counterfeit

- Copied labels

- Copied shoulder labels

- Fill level is too high

- Cork is too faint to read.

- Magnum of Romanée-Conti 1937: Counterfeit

- From a distance, looks good, but label has been photocopied

- Capsule finish is too rough and has not been done professionally

- Capsule would not have been applied by DRC for this wine.

- Pink wax is not appropriate to DRC

Two bottles that were purchased by Michael Fascitelli were then examined:

- Magnum of La Tâche 1934: Counterfeit

- Photocopied label

- Capsule roughly applied

- Seal on top very indistinct, and letters missing

- Methuselah of Romanée-Conti 1971: Counterfeit

- Label is a good copy, but printing is too flat, and green around appellation is indistinct under magnification.

- Capsule very poorly rendered, with a very faint seal.

He then moved on to Don Stott’s wines.

- Roumier Bonnes-Mares 1929: Counterfeit

- The name G. Roumier would not appear on a wine of this age

- There is a watermark on the label paper reading “Concord”. This is the paper of a printer based in Indonesia, established in 1983.

- Roumier Musigny 1962: Counterfeit

- The label is a copy

- Capsule is a generic Burgundy capsule

- Paper is Concord

Egan noted that he had heard Christophe Roumier testify and say that he believed that several of the Roumier wines presented to him were fake; Egan agreed with that assessment.

Egan then looked at the bottles consigned to the Spectrum auction in London in February 2012. He had previously examined these bottles for a client. This was a quick look at 120 bottles; he had only a few hours and very poor lighting conditions, but did find several counterfeit bottles. Egan confirmed that this examination was before Kurniawan’s arrest in March 2012.

- Magnum of Romanée-Conti 1978: Counterfeit

- Label is a copy

- Stamp of the number is wrong because from 1978 serial numbers were actually printed on the labels

- UK importer’s address is incorrect: Sackvilee instead of Sackville. This matches a range of labels recovered at the defendant’s house with the same error.

- Cork has very little discernible on it. A real cork would have the vintage and name “Romanée-Conti” on it.

- Two magnums of La Tâche 1971: Counterfeit

- Labels are copies, with very flat printing onshoulder and main labels

- The stamped numbers are not authentic

- The fills are two high for the age

- Branding is not well executed on corks, showing that the corks are not authentic

- DRC Montrachet 1966: Counterfeit

- Copied label, with flat printing.

- Label has been treated to simulate age.

- Nicolas stamp is not well done, and “Reserve Nicolas” neck label was found in quantity in Rudy’s house, as was the “Ce vin doit etre decante” label.

- The capsule is foil, with Nicolas on it, and looks like an actual Nicolas capsule

- The stamp on the cork matches the stamp found in Rudy’s house and the template on the computer testified about previously.

Egan testified that this wine in particular was very cloudy, and didn’t look very healthy. He confirmed that his conclusions for the other seven Montrachet bottles in evidence were the same.

- De Vogüe Musigny Blanc 1945: Counterfeit

- Copy label that has been distressed, by tearing and rubbing.

- Very badly applied Nicolas stamp.

- Branded cork that matches a stamp found in the house

- De Vogüe Musigny Blanc 1962: Counterfeit

- Copy label with very flat printing.

- Very crude branding on the cork

- De Vogüe Musigny 1945: Counterfeit

- Copy label.

- Very badly applied Nicolas stamp.

- “Ce vin doit etre décanté” label in the wrong position

- De Vogüe Musigny 1962: Counterfeit

- Copy label with very flat printing.

- Serial number is well done

Egan explained that when he said the printing was flat, what he meant was that the domaines had printing that made the ink very precise, with very dark print. The labels he saw on the wines today were all very matte, without the slight shine one gets on a real label.

Hernandez asked Egan if he had heard Laurent Ponsot testify about Domaine Ponsot bottles that Ponsot thought were counterfeit. Egan confirmed that he agreed with Ponsot’s assessment.

Egan then testified that he had made a list of all wines from various clients who had purchased directly from the defendant, and has concluded that there is a substantial quantity of counterfeit wine just from his own personal client list. In particular, two clients purchased 39 counterfeit bottles from THE Cellar I alone, which cost nearly $1.3m.

Since 2006, Egan has checked thousands of bottles of wine. Of these, he has found 1,433 counterfeit bottles. Of the counterfeit bottles, 1077, or 75%, came from Rudy Kurniawan. The largest purchasers of fake wine from Kurniawan were Michael Fascitelli and William Koch.

Egan then broke down the most highly faked wines, the highest by far being DRC (284), followed by Roumier (140), Ponsot (118), Pétrus (92), de Vogüe (65) and Mouton Rothschild (45).

Michael Egan, cross-examination

Jerome Mooney began the cross-examination of Egan by asking him initially about his time at Sotheby’s, and examining the condition of the wines. He then directed Egan’s attention to the Montrachet wines, which they agreed looked like they could be samples from the urology department at Mt Sinai Hospital. Mooney asked if Egan knew how the government had stored the wines, and Egan replied he did not. He agreed that storage was vital – too hot, the wine is going to slowly cook. He agreed with Mooney that leaving a box of wine out on a shipping dock in the sun was not a good thing, nor would standing it on top of the air conditioner, because of the vibrations. He also agreed that sunlight was damaging to wine.

Mooney suggested that Egan had found only a couple of bottles when he inspected the bottles at the Spectrum auction; Egan said he believed that those were the one he mentioned to the Spectrum staff at the time. However, he only had two hours, and 120 bottles, which was a breakneck pace and was in itself only a small selection of the bottles for the auction.

Mooney then noted that Egan had already testified that the auction market had grown from $19m to $300m; Egan corrected him and emphasised he had said $90 million in 2002, and $300m in 2007. Mooney suggested that such an increase in volume would naturally lead to an increase in counterfeits, even with auction houses checking. Egan responded that he thought the auction houses were checking wines (probably because he worked for one that did), but that a lot of counterfeit wines are also coming from wine merchants and private sales.

Mooney then asked whether, when inspecting wine for Sotheby’s there were labels that sometimes came off the bottles, and Egan confirmed this happened. In his early years at Sotheby’s there were a couple of instances where damaged labels were sent back to the chateau for new ones. From time to time, there would be a different label on a bottle to identify it, but this would be noted in the cellar records. If someone came off the street with a Xeroxed label, then Sotheby’s would not sell the wine. If it were in their records, then they would, but would note that it had no label, and but that from cellar records it had been identified as whatever it was. He emphasised that these labels would not have any sophistication to them – they would probably be just a tag hung around the bottle. Mooney suggested that the “1899 RC? / 1875 ?” on one of the bottles was simply someone trying to figure out what the wine might be, and not any attempt at fraud. Egan confirmed the bottle and fill were appropriate for age, as was the sediment.

Mooney then noted that as the auction market had grown, one of the major places it had done s was in Asia, and that many auction houses are becoming more active in Asia. Egan confirmed this, and emphasised Hong Kong. He had not been involved in any Asian auctions, although some people in Asia had asked him to authenticate their wines.

Egan confirmed that, while part of Grand Cru Wine Consulting he authenticated wine for a client he now understands to be Fascitelli. He was asked to give an opinion on a large number of bottles that he understood had been purchased in THE Cellar I. Mooney highlighted the report that Egan had produced, including a bottle of Allonge. He then directed Egan’s attention to Fascitelli’s invoice for THE Cellar I, which did not contain any bottle of Allonge. Mooney then argued that this bottle was not, therefore, purchased from that auction or from Kurniawan, which Egan accepted.

Mooney then highlighted the nine bottles of Chateau Haut-Brion 1959, which Egan had, in his report, said appeared genuine, as did 10 bottles of 1966 de Vogüe Bonnes-Mares, and a number of further lots, including a magnum of La Tâche. There were four bottles of Hermitage La Chapelle 1961 that had probably been reconditioned at Jaboulet, and the report suggested that Paul Jaboulet Ainé, the company that produces the wine, should be contacted. There were also a number of bottles on the invoice that were not covered in his report.

Similarly in his report for THE Cellar II, there were a number of bottles that appeared authentic, and some bottles in the report that did not appear on the invoice for that sale. There were, in fact, a great many more bottles in this report that did not appear on the invoice.

Mooney then highlighted that Egan’s conclusions about what percentage of fake wine had come from Kurniawan had been based on the assumption that the information provided to him about the source of wine was correct, but that, as he had just shown, that could not necessarily be relied upon.

Mooney then directed his attention to the Caveau de la Tour purchases, of older Burgundies. He argued that €60 / bottle is not exactly cheap, translating at the time to about $75 to $80 per bottle. Egan agreed that that was not cheap. Mooney asked if Egan had clients who can afford to drink a $3000 or $4000 bottle of wine each night, which Egan confirmed. Mooney asked if Egan could do that, and he replied “in my dreams”. He also noted that even his wealthy clients would sometimes drink a $10 bottle of wine. Mooney then said that we would expect an individual to purchase wines that he would like to drink. Egan agreed, but stressed that for immediate consumption, that would not be hundreds of bottles. Mooney then said that they had heard that Kurniawan would buy and buy and buy – he could not stop himself. Egan said that he had heard that Kurniawan was a large buyer, but not of wines like these.

Mooney then addressed the wines found in Kurniawan ‘shouse like the Marcassin. They agreed that at $200/bottle, this was not a cheap wine.

He then turned to an email from the broker regarding the old Burgundies Rudy was buying, which had a claim from the broker that “Broadbent” had given both vintages four out of five stars. Mooney pointed out that Michael Broadbent worked for Christies, Sotheby’s competition. Egan noted that Broadbent had liked the vintages, not the wines.

Michael Egan, re-direct

Jason Hernandez redirected for the Government. He first referred back to the report that Egan had prepared for Michael Fascitelli. Egan confirmed that the wines to be examined were selected by Fascitelli or one of his representatives. There were a number of wines that Fascitelli had bought that he did not examine, and he therefore has no opinion as to the authenticity or otherwise of these wines. Jason Hernandez then went through the report, highlighting the counterfeit bottles that were identified. These included:

- 10 bottles of 1947 Cheval Blanc

- 11 bottles of 1947 Lafleur

- 11 bottles of 1982 Lafleur

- 6 bottles of 1947 Latour à Pomerol

- 2 magnums of 1961 Latour à Pomerol

- 12 bottles of 1947 Pétrus

- 4 bottles of 1961 Trotanoy

- 1 magnum Henri Jayer 1978 Richebourg

- 2 bottles 1978 Jayer Cros Parentoux

- 1 magnum 1934 La Tâche

- 6 bottles 1962 Roumier Bonnes-Mares

- 4 bottles 1962 Rousseau Chambertin

- 2 bottles de Vogüe Musigny 1962

There were, therefore, a mixture of counterfeit and real bottles.

Hernandez then showed Egan the post-sale report for Fascitelli for THE Cellar I. The invoice indicated that Fascitelli was bidding not only under Paddle 87, but also Paddles 184 and 1285. None of the 1285 wines were inspected, because they were all Italian, but Egan believed he had inspected some of the Chambertin Rousseau from 184, and a number of wines from Paddle 87.

The invoice from THE Cellar II was just for one paddle, but Hernandez reminded Egan that Truly Hardy had testified at the beginning of the week that Fascitelli had bid under several paddle numbers.

Hernandez then asked Egan to confirm that there was only one Methuselah of Romanée-Conti 1971 sold in THE Cellar II, which Egan did. They then examined exhibit 5-3, which had a sticker on the back identifying it as a lot in THE Cellar II sale, by Acker Merrall & Condit. Egan said this indicated that the bottle was acquired from that auction, possibly by another paddle number used by Fascitelli.

Egan then confirmed that there were quite a few counterfeit wines that he found when examining the purchases from THE Cellar II.

Hernandez then asked about the examination of 120 wines at Spectrum in two hours. He asked if 1 minute per wine was normal for Egan; Egan replied it was anywhere from 20 minutes to one hour per bottle. He did not at the time catch the “Sackvilee” misspelling, but took a photograph of the bottle and caught it then.

Egan then explained that chateaux replacing labels happened very rarely – perhaps three or four times, no more than that, and not later than 1982. If a consigner had put photocopied labels on a wine, that would need to be disclosed. The circumstances would be that the original labels had deteriorated so badly that they are illegible, but that the auction house and vendor have identified the wine to be correct.

Turning to the older Burgundies bought, Egan reiterated that the wines were not rated by Michael Broadbent, just the vintage. He added that he did not think Broadbent would ever have rated 1971 Patriarche Meursault-Charmes as four stars; he would probably have given it a minus. If he were advising a client, he would advise them to buy no bottles at all.

Michael Egan, re-cross

Mooney asked if Egan had inspected any of the Patriarche bottles. He replied that he had only seen the magnum of Corton on display. Mooney stated this meant that Egan would not know how drinkable these wines were. Egan replied he hadn’t sampled them.

Click here for part 13.