The Trial: Part 3

Rudy Kurniawan’s Trial

A Multi-Part Feature on the trial of Rudy Kurniawan, including the transcripts, testimony and evidence that put the largest wine counterfeiter of our time behind bars.

THE TRIAL - PART 3

DAY 3: WEDNESDAY 11TH DECEMBER 2013 (CONTINUED)

Witness: Trenton Schmatz, FBI

Jason Hernandez questioned Special Agent Trenton Schmatz, a computer forensic examiner with the FBI, responsible for the collection of digital evidence. He testified that he had examined the computers and other electronic devices and digital files that the FBI had collected from Rudy Kurniawan’s house. He testified that in examining evidence, the FBI will remove a hard drive, attach it to a write-blocking device, which blocks any data being written to the original evidence, and then generate an image of the evidence onto a forensically cleaned server.

They then use a piece of software called FTK (Forensic Tool Kit) that will identify individual types of evidence and collect all those together – so for example, all deleted files, or all spreadsheets. It can also identify individual items, such as words or phrases, and can collect all files containing such phrases. An agent will then burn the items that are found to be potentially relevant to his case to a disk, including not just, for example, a picture, but metadata about when the file was created, when it was modified, etc.

DAY 4: THURSDAY 12TH DECEMBER

Witness: Trenton Schmatz, FBI (Cont’d)

Jason Hernandez directed Agent Schmatz’s attention to Exhibit 14-3, a collection of different documents taken by Agent Wynne from the FTK report for one of Rudy Kurniawan’s computers, which contained 610 different images. They showed five of these to the court.

They then examined the FTK file for the images in this exhibit, which gave information the drive it was in, the date the image was created on that particular computer, the last date it was modified, and the last date it was accessed. Reading down the first page, it was clear that the majority of dates on this page at least were created or modified in 2004 or 2005.

SA Trenton Schmatz, Cross-Examination

Mr Mooney queried exactly which exhibit came from which detvice; counsel conferred off the record, and agreed. Mooney asked if Agent Schmatz remembered the BlackBerry Torch; he replied that he did, but that he did not personally do the examination on it. Mooney asked if what Agent Schmatz was saying was that he did not know whether what was on this device was accurately collected and put into the exhibit. SA Schmatz replied that he was simply saying he didn’t do the examination, so it was difficult for him to answer any questions on the examination. It had been password protected, and was sent to the headquarters lab which conducted the examination.

The Government and the Defence agreed a stipulation that the Government Exhibit 12-9-A contained in electronic form true and accurate copies of electronic documents and other information stored in the electronic memory of the BlackBerry Torch.

Mooney commented that there were over 200,000 files on the discs, and that a very few had been selected – for example, 610 on the Sony Vaio in Exhibit 14-3. Schmatz agreed that there could be lots of other things on these devices.

Witness: Laurent Ponsot

Laurent Ponsot, manager and co-owner (with his sisters) of Domaine Ponsot in Morey St. Denis, Burgundy, took the stand, and was questioned by Jason Hernandez for the US Government. He has worked in the winery since 1981, and took over from his father as manager in 1992. His father had been head of Domaine Ponsot for approximately 35 years, and his grandfather, Hippolyte Ponsot, from 1922 until 1958. The Domaine was started in 1872 by William Ponsot, and it has been in the family since then.

M Ponsot explained the concept of estate bottling – meaning that the wine is put into bottles at the winery. He noted that for centuries wine in Burgundy was traditionally made by the winemakers, and sold in barrels to the negociant, who would age for one or two years, bottle it and sell it under his own brand. This system continued until the early 70s in most of Burgundy, but Domaine Ponsot was one of the first wineries to do estate bottling, in 1932.

M Ponsot then explained the classification hierarchy of Burgundy, from basic Bourgogne, through Village, Premier Cru and Grand Cru, which represents only 2% of the area of Burgundy but 1% of the production. Domaine Ponsot owns land in 22 different appellations, some in each category, but in particular 12 Grand Cru that represent nearly 80% of their production. It has made these wines from the beginning, although the legal classification only started in 1936. Laurent Ponsot’s grandfather, Hippolyte, was the first to start writing notes about the need to classify the vineyards, and was instrumental in creating the regulations with other winemakers. These are now part of the laws of France.

Mr Hernandez then showed M Ponsot a map of Morey St. Denis, and M. Ponsot explained the concept of an appellation to the court, including the different hierarchical levels. He identified two of the Grand Cru appellations: Clos de la Roche and Clos St. Denis, both of which are produced by Domaine Ponsot.

Domaine Ponsot sells wine in 48 countries – up to a maximum of 8% in any one country, although some get far less. He does not need to promote the wines, as the demand is much higher than his potential production – he has counted 45 requests per bottle.

At the Domaine they keep a stock of older wines, together with some older wine labels, dating back from his grandfather’s time. He regrets that there are fewer older bottles than he would like – his ancestors liked to drink! There are now only about 1000 bottles of older wine.

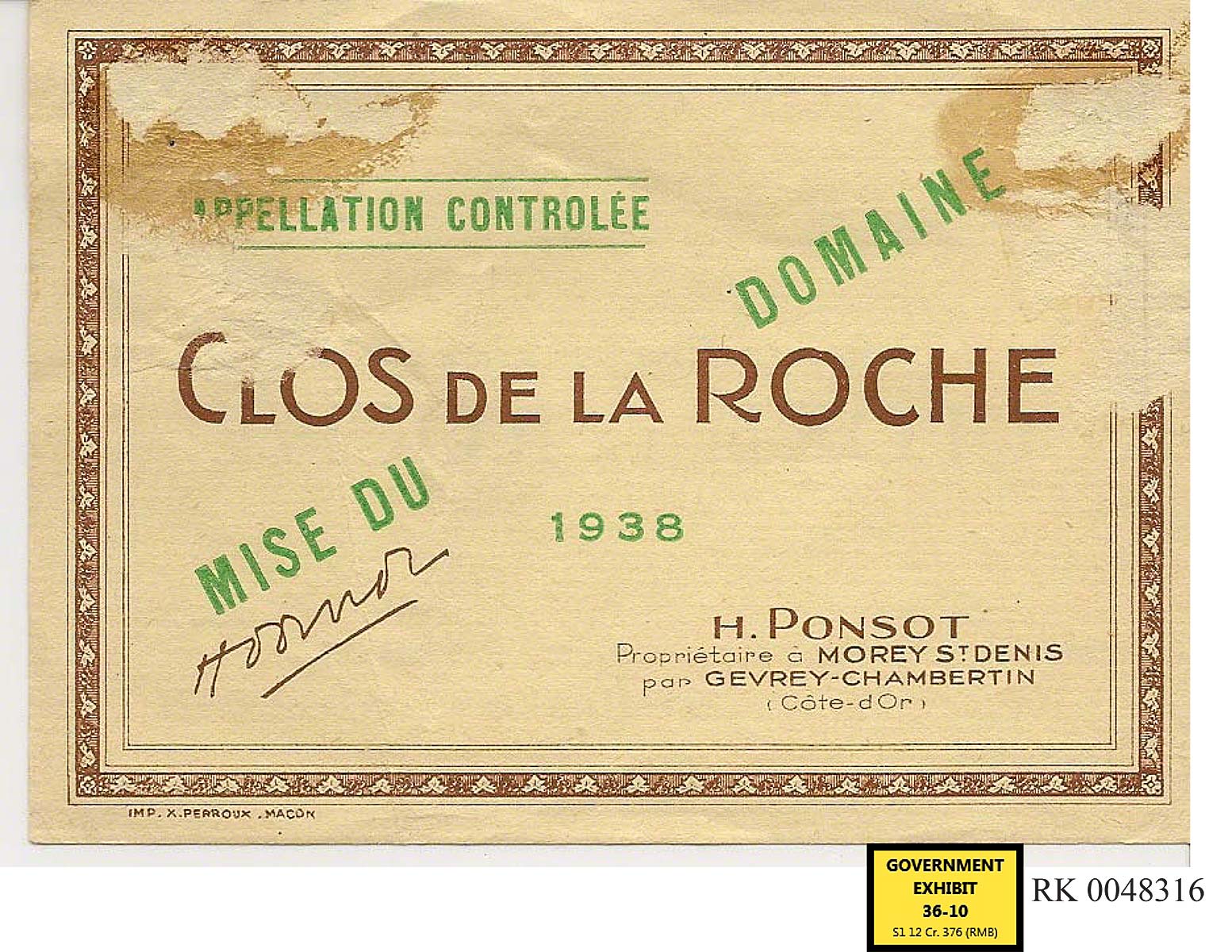

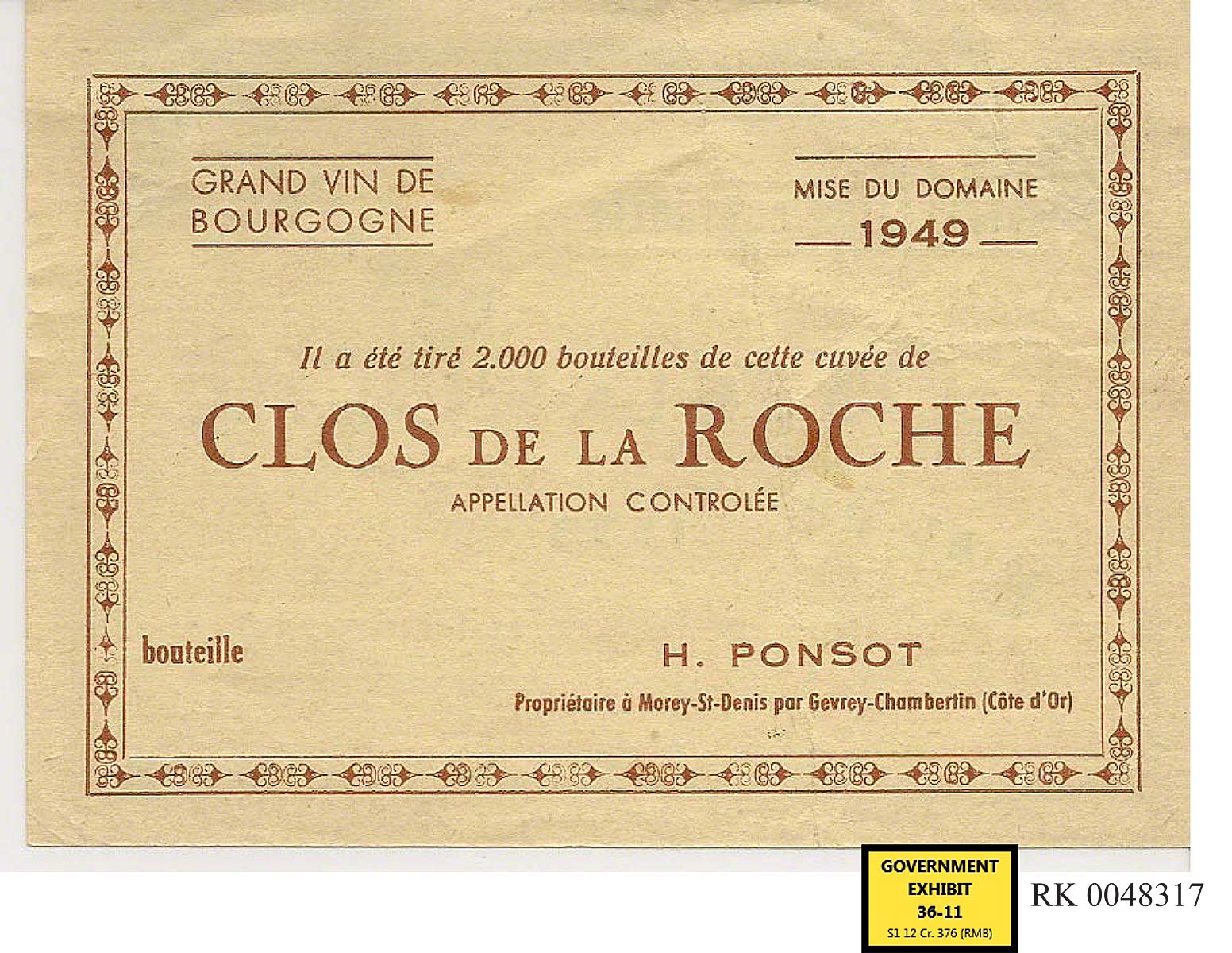

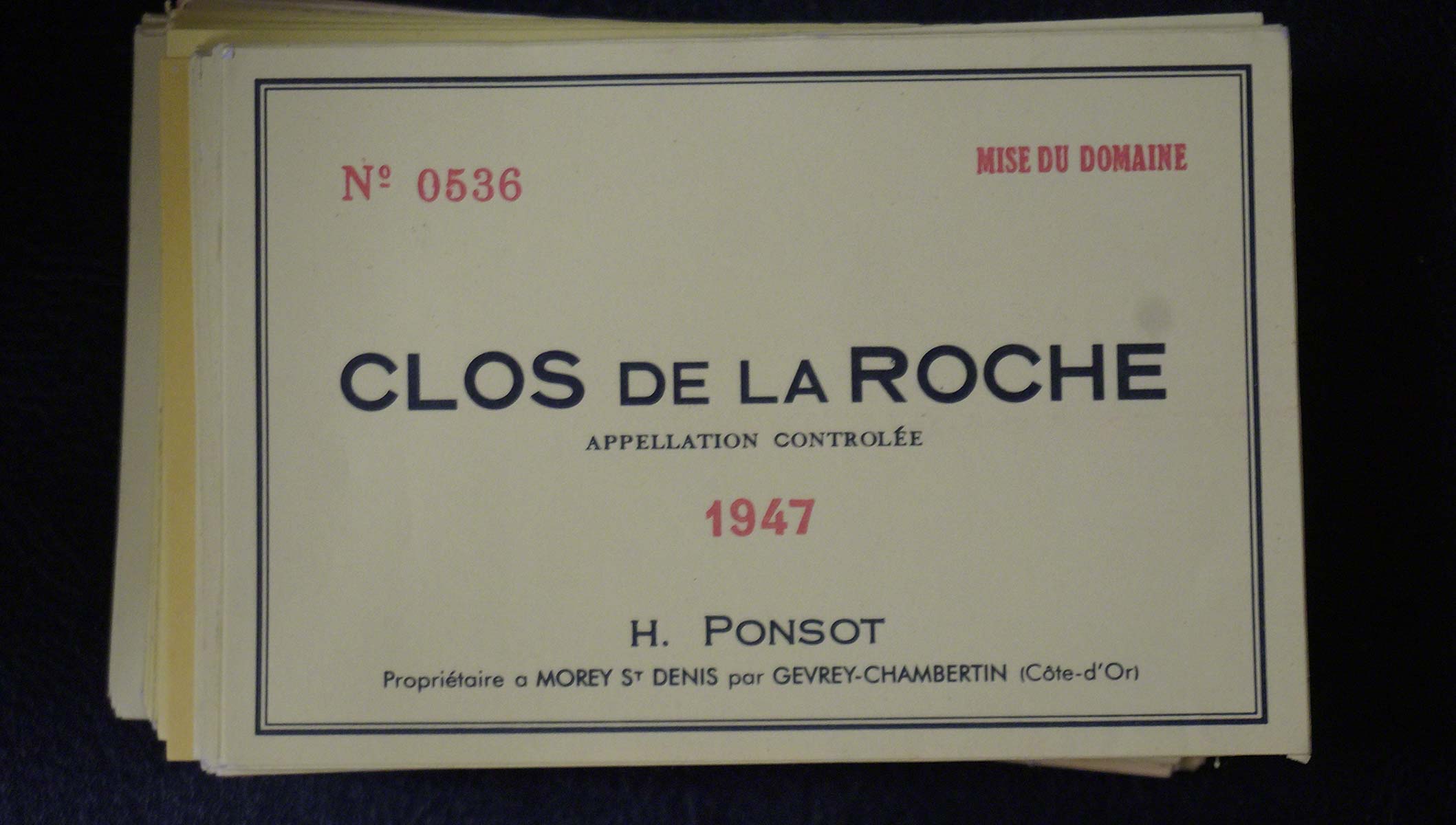

Mr Hernandez asked M Ponsot if he recognised two labels – he agreed that these were labels used by his grandfather, and which he had provided to the FBI in connection with this case.

The first label, Clos de la Roche 1938, was the second year that a bottle could have “Appellation Controlée” on it. The labels were all hand-signed in the lower left hand corner by Hippolyte Ponsot, which he would do each night.

The second, a 1949 Clos de la Roche, was of the type used during the 40s and 50s. For the first time, there is an indication of the number of bottles made of this particular wine – in this case, 2000.

Hernandez then showed the Court three photographs. The first was of the row of the oldest bottles in the Domaine Ponsot cellar.

The second was a closer look at the boxes they keep the oldest wines in. All of these wines (those older than 1970) were recorked in 1985, at which point they also put wax on them.

The addition of wax to the very old bottles is to reduce further oxygen ingress through the cork.

Prior to 1985, no Domaine Ponsot wines were sealed with wax. The 1985 recorking was the first and only time wax was used.

Mr Hernandez then showed Laurent Ponsot Exhibit 181, similar to the item below.

M Ponsot categorically stated that these were not authentic Domaine Ponsot labels. It was too yellowish, not looking like the authentic 1940s label as shown above.

He confirmed that Domaine Ponsot labels were applied with glue – effectively, exactly the same as wallpaper glue, and they stick them on by hand. In 1989, they began using self-adhesive labels.

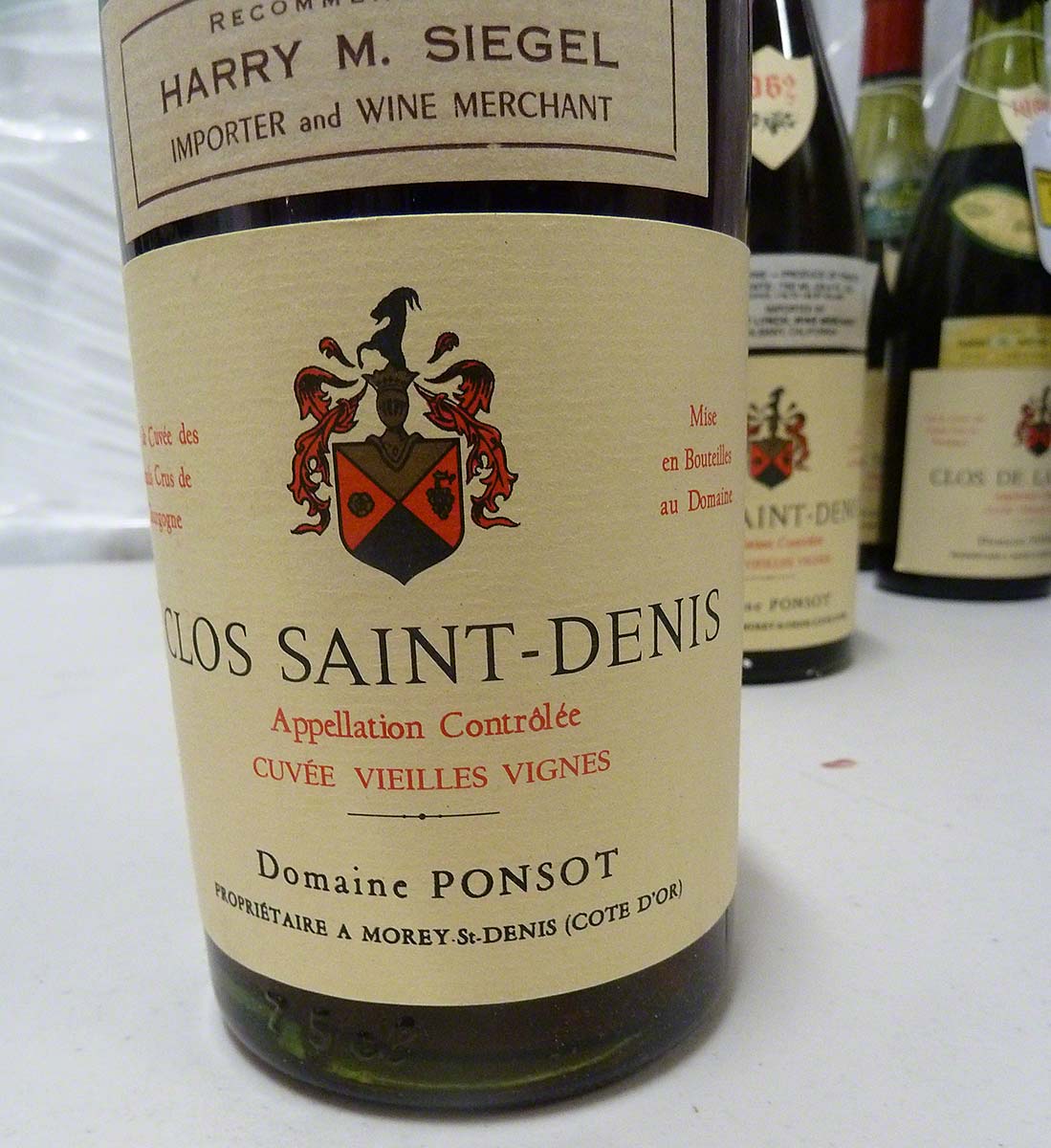

Exhibit 1-140 does look something like a real Ponsot label, and was similar to the item below.

However, these were used mainly in the late 50s, 60s and early 70s, and would have included the name and initials of Laurent Ponsot’s father.

Laurent Ponsot confirmed that the Domaine had never given permission for anyone outside the Domaine to make Domaine Ponsot labels and apply them to bottles.

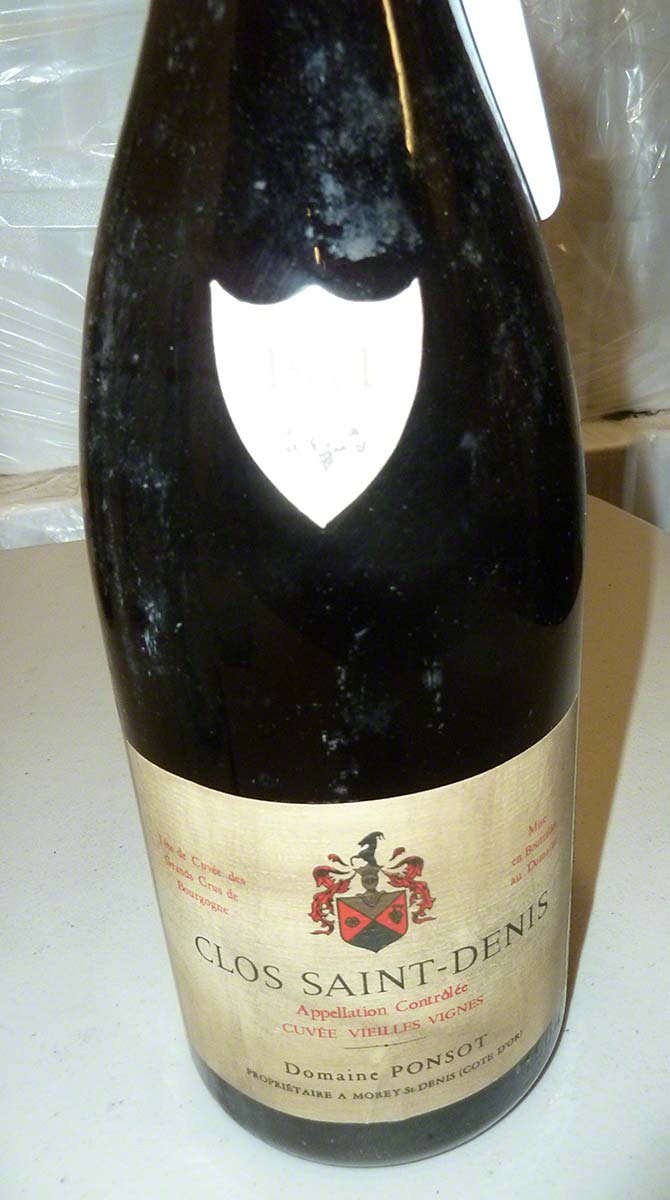

Jason Hernandez then asked Laurent Ponsot how he became aware of the April 2008 Acker Merrall & Condit (AMC) auction. M Ponsot replied that his friend Doug Barzelay asked when he started producing Clos Saint-Denis. He replied “Why are you asking?” Mr Barzelay sent an immediate reply saying there was an auction in Manhattan in two days’ time in which they were selling vintages of Clos Saint-Denis from the 1940s, 50s, 60s and 70s. Laurent Ponsot returned to the winery in 1981, just after the harvest, because his father had the opportunity to add to the winery portfolio by working the Clos Saint-Denis Appellation, which a rich person from Paris had just bought. The Ponsot family would work on the vineyards and make the wine, and in return give one-third of the bottles to the vineyard owner. Laurent Ponsot came back specifically because of this opportunity, and 1982 was the first vintage they made. There are no vintages before 1982 of Domaine Ponsot Clos Saint-Denis.

M Ponsot said he was quite shocked when he had the email, and asked for the catalogue by email, which Mr Barzelay sent. Looking at the pictures, he knew that “everything was not authentic”. He asked Doug Barzelay to whom he should speak, and was told to call John Kapon. M Ponsot called John Kapon and spoke with him twice, eventually receiving agreement that the wines would be withdrawn. However, Ponsot doubted it was a true agreement, calling it “a yes to end the conversation”. As a result, he took a plane the next day, arriving at the auction 10 minutes after it had started. The wines were in the room – many people had already seen them. M Ponsot saw someone point him out to John Kapon, and tell Kapon why he was there. At this point, when it came to the Ponsot wines, Kapon announced they had been withdrawn at the request of the winery.

Mr Ponsot then examined some bottles. The first, Exhibit 8-22, purported to be a 1945 Clos Saint-Denis.

M Ponsot reiterated it could not be a 1945 Ponsot Clos Saint-Denis because that did not start until 1982. In addition, they did not sell any wine to Nicolas. They also did not use the wax on the bottle. But the latter two points are irrelevant because, simply, the wine cannot exist. It was not made in 1945. He added that the wax was a different colour to that used in 1985 (the only time wax was used at the Domaine).

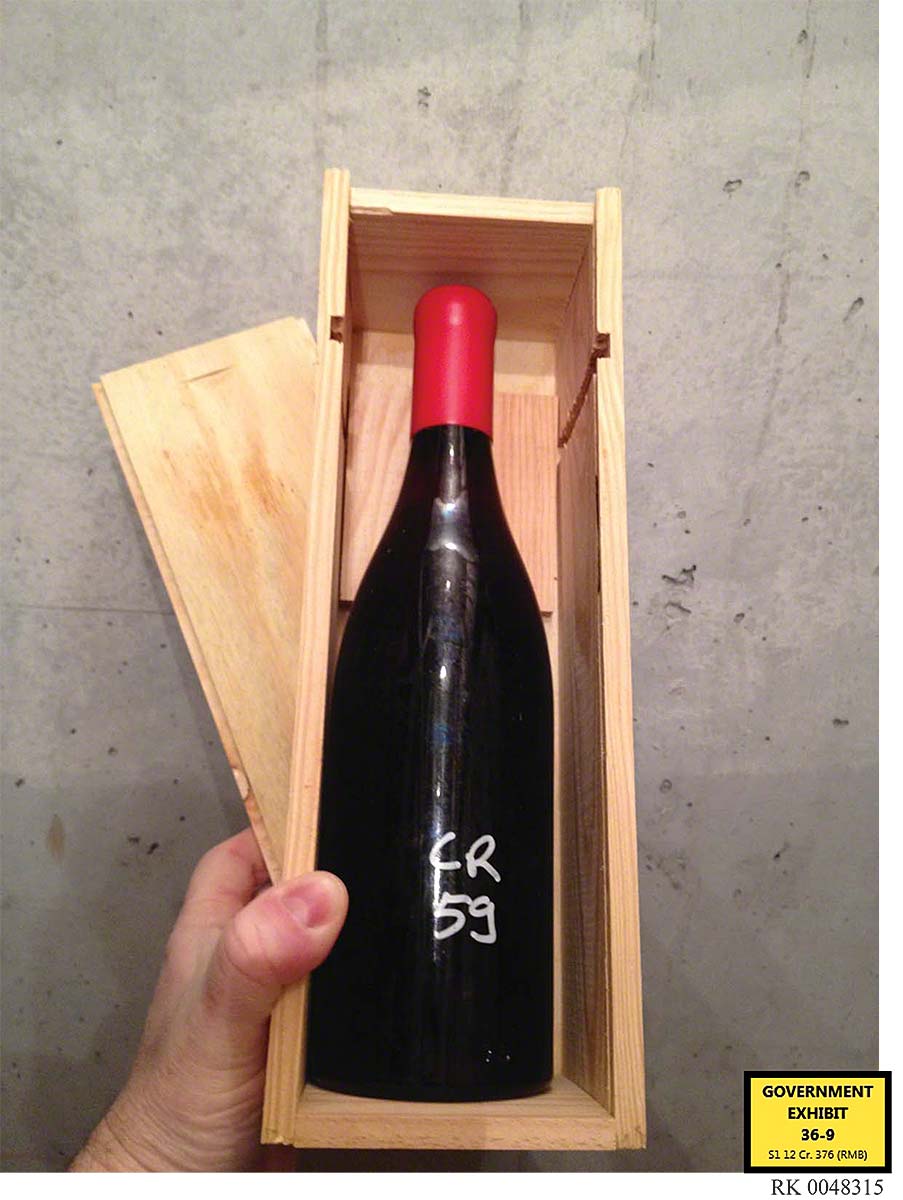

The next, Exhibit 8-24, was also of a pre-1982 Clos Saint-Denis, 1959 this time.

It had a capsule saying imported by Alexis Lichine, who has never been the Ponsot importer, and a label saying it was selected and recommended by a wine merchant of whom Laurent Ponsot had never heard.

The next was a third Clos Saint-Denis, this time from 1962. The Frank Schoonmaker label cannot match with 1962 (ignoring the vineyard issue) because he retired before that.

Having looked at the Clos Saint-Denis wines, Hernandez directed Ponsot towards the Clos de la Roche. The first one was dated 1927, and, as Ponsot reminded the court, this could not exist because the Domaine did not start bottling its own wines until the 1932 vintage. It also says Appellation Controllée, before such a thing existed, and was sealed with wax.

The next two Clos de la Roche could, at least, in theory exist, being 1937 and 1945, but the label is not at all like the labels used at that time. The 1939 bottle also had a gold capsule, which has never been used.

And then Exhibit 8-33, which did have the right type of label. However, the back label implied it had been sold by Nicolas, which never happened. Ponsot also said it was easy for him to see it was a copy that has been dirtied to make it look more authentic and old. The paper is different to the type of paper the domaine used.

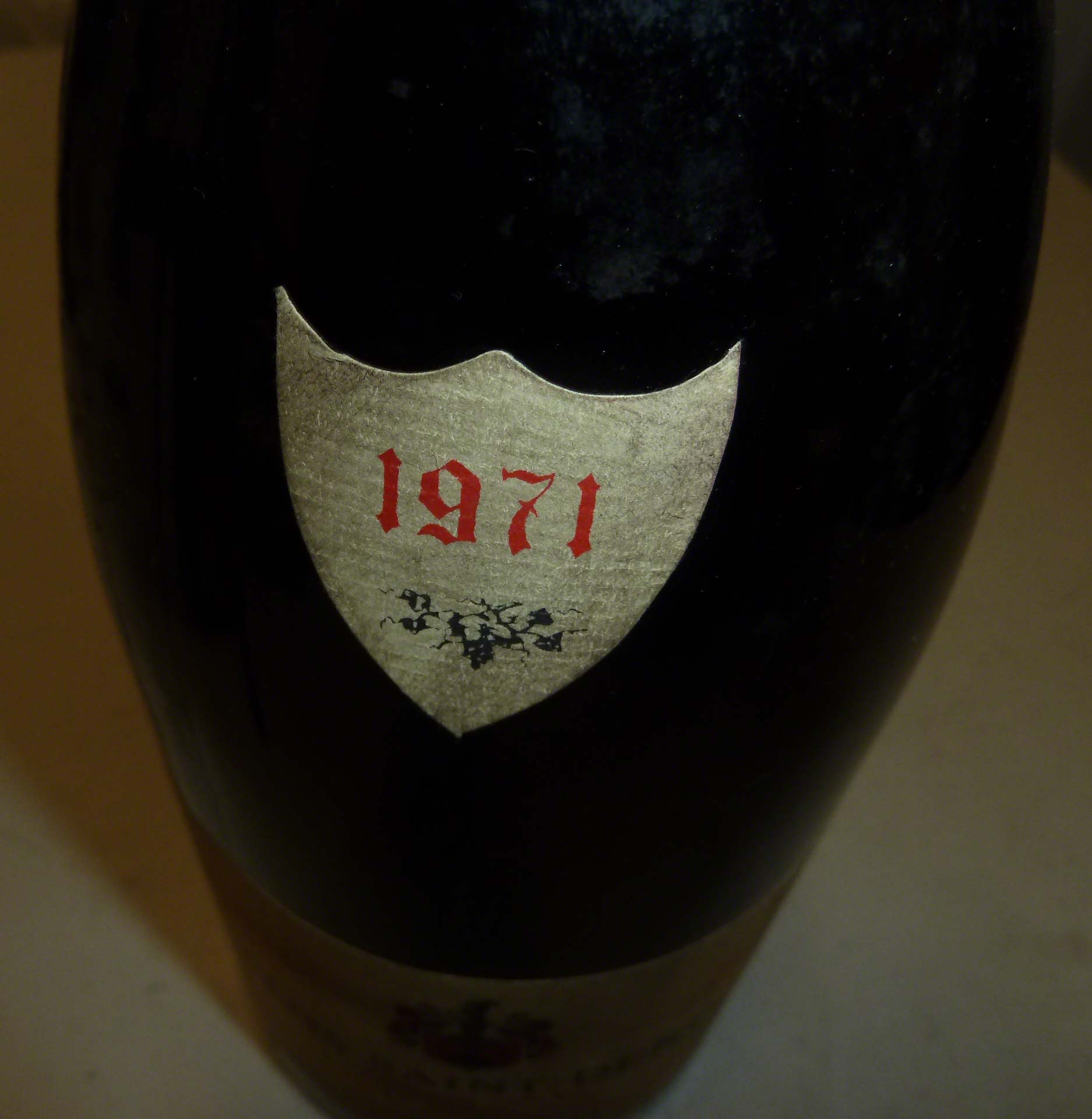

Hernandez then asked Ponsot to look at another set of government exhibits, this time not from the October 2008 AMC auction. These purported to be Clos Saint-Denis Domaine Ponsot wines from 1971, 1962 and 1959. Hernandez asked if, considering the three bottles together, Ponsot could say anything about their authenticity. Laurent Ponsot replied that it was obvious – the wine was first produced in 1982, so these could not be real. In addition, the capsules were not genuine, and the importer was wrong for the time.

Hernandez then directed Ponsot’s attention to three larger format bottles, Clos Saint-Denis from 1971, 1962 and 1959. He asked if it was the same result, which Laurent Ponsot confirmed.

After returning to the witness stand, Laurent Ponsot replied to Hernandez that he had a lot of people coming to speak to him after the auction, and he learned through them that the owner of the bottles was Rudy Kurniawan. He did not know of Rudy Kurniawan, but Doug Barzelay told him that Kurniawan was at the auction, and arranged for Ponsot to meet him at a lunch the following day, with John Kapon and Doug Barzelay also present.

At the lunch, at Jean-Georges, Ponsot asked Kurniawan almost immediately:

“’Where are the bottles coming from? Can you give me the way you bought them? Where did you get these bottles?’ And so at that moment I saw Mr Kurniawan watching his plate and saying ‘I don’t know. I buy so many bottles that I cannot remember where the bottles are coming from.’

“I was suspecting that something was bizarre because when you have such an answer from someone which can have in his hands 84 bottles of old wine from Domaine Ponsot – which is very, very rare.”

Kurniawan continued watching his plate – there was no eye contact after this question. M Ponsot decided he did not want to press further at that moment – he wanted to think about it, and decide what he would do further.

At the end of the lunch, Kurniawan gave Ponsot his email address, and Ponsot sent him an email a bit later, 16th May 2008, asking Kurniawan about the provenance of the wines, and saying he would like to meet when next in Los Angeles, in July. Kurniawan replied on 5th June (i.e. three weeks later) saying that he would love to meet, and that he bought the wines from the cellar of Pak Hendra in Asia.

Ponsot remarked that he was happy to have a name, but that Asia is quite wide. He had never heard of a Pak Hendra, despite selling quite a bit in Asia from 1982, and knowing many many collectors and wine merchants in Asia. He also asked around to see if anyone knew of a Pak Hendra.

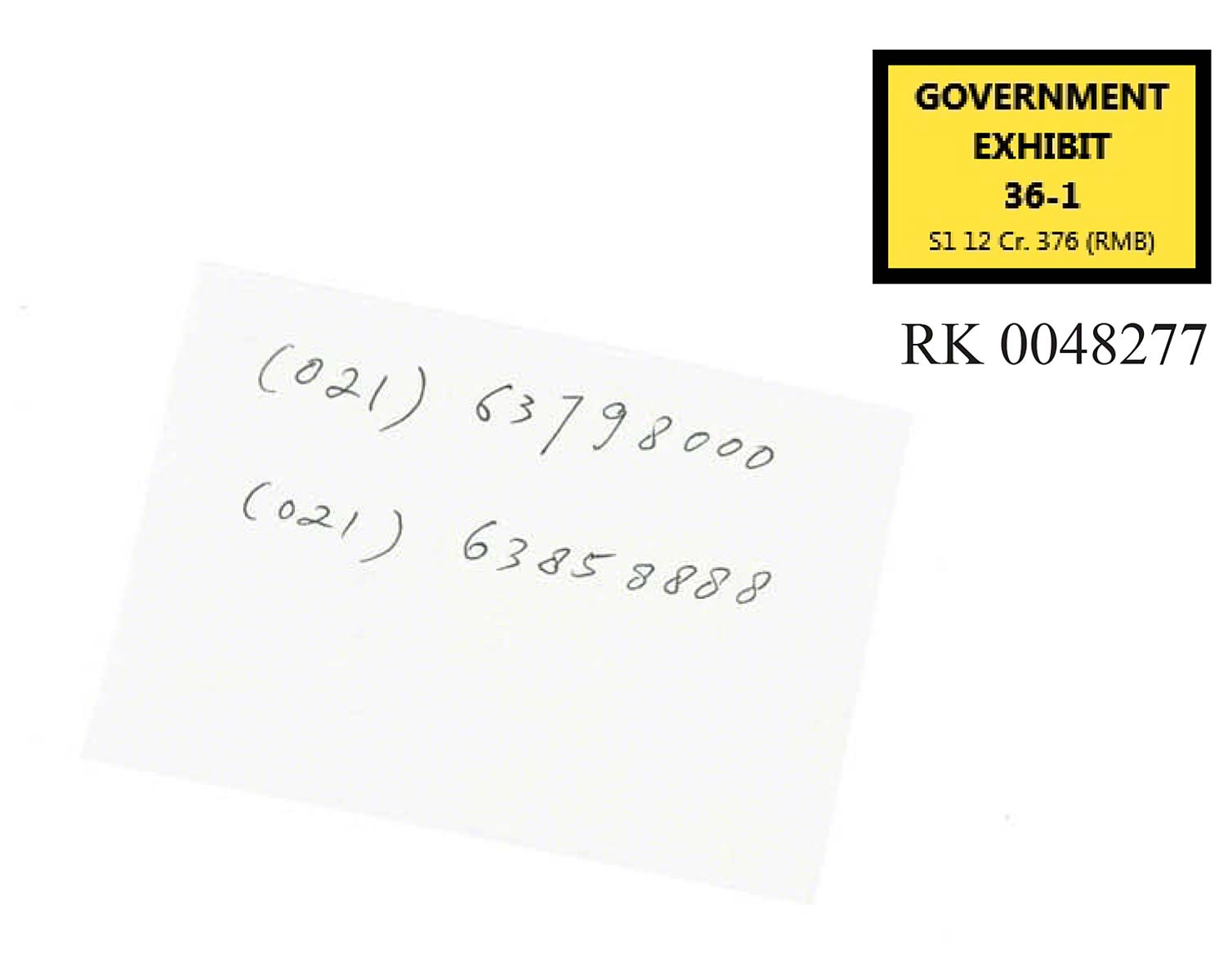

In July 2008 Laurent Ponsot met Rudy Kurniawan for dinner in Los Angeles. Kurniawan showed up with two bottles – a white wine from Domaine Ponsot and a 1955 La Tâche from DRC. Despite the wine, Ponsot was focused on the source of the wine, so asked for more details. Kurniawan gave him two phone numbers, written down on a piece of paper, saying “this is in Jakarta”. Ponsot said that Kurniawan was less uncomfortable than the first time they had met, and, since Kurniawan had now given him two phone numbers, Ponsot was thinking he should be happy with that.

Hernandez then asked the court to show Laurent Ponsot Exhibit 36-1, which Ponsot recognised as a copy of the two phone numbers. He confirmed that he saw Kurniawan writing the numbers in front of him at the table over dinner in July 2008 at Il Grano in Los Angeles.

Ponsot tried several times to reach one of the numbers, which had no answer. The other was a fax machine, so he only tried that once. His reaction then was that Kurniawan was lying to him. He then learned from a friend in Singapore that Pak simply means Mister, and that Hendra is a very common surname in Indonesia

Jason Hernandez then showed an archived website page, from July 13 2008, showing that the numbers given were for the call centre for low cost Indonesian airline Lion Air.

Hernandez asked Laurent Ponsot if he had seen Kurniawan again after that meeting in Los Angeles. M Ponsot confirmed that he saw him in May 2009 in Los Angeles, again at a dinner, organised by Laurent Ponsot himself. Ponsot told Kurniawan that he could not reach any person at the phone number, and that he needed information he could follow, “the real truth”. Kurniawan promised that the next day he would provide information by email with all the details of the providers; the email was never received.

After the wines were removed from the AMC auction in April 2008, Ponsot knew that there was something bigger at work than some random rogue bottles. [Interesting, one thinks. If he knew this, how could others purporting to be experts in provenance ignore it? But I digress.] His first reaction was a bit of pride, that someone wanted to fake his bottles. This quickly gave way to anger, because he knew that it was not good for the reputation of the winery.

Ponsot was also particularly upset that it was dirtying the reputation of Burgundy, which was built on terroir, and so “My idea was to try to wash the integrity of the terroir of Burgundy.” He therefore decided to start a “crusade” against the fakers – although he commented that initially he was more like Don Quixote, tilting at windmills. To do this, he accepted all possible invitations to try to drink the most possible wines, and when he found one suspect, to follow the link to find out where the wine is coming from, and so on. He did this over two years, and estimates that it cost him €120,000.

Laurent Ponsot, cross-examination

Jerome Mooney opened the cross-examination by asking Laurent Ponsot if there was a rationale for when a wine would be put into a large format bottle. Ponsot replied that the vast majority of wines would be in the 750ml bottle; two to three percent, to a maximum of 10%, might be in a magnum, and formats larger than that are very very rare. For Domaine Ponsot, Jeroboams and Methuselahs were started in 1993, although they have always done magnums, because the wine has the ability to age better in magnum.

Mooney then asked about the early period of the vineyards, and confirmed that most of the wine was sold in barrels. He noted that 1932 was the first year that Domaine Ponsot was doing estate bottling, but that it was not the first time they produced wine, which was in 1872. He commented that the vineyard would have still had bottles back in those early periods, which Ponsot denied. Mooney questioned whether these were not even for themselves, or to sell to restaurants; Ponsot replied that there were none. Mooney at this point then noted that Laurent Ponsot was not actually there in 1932, and there are no records of sales to restaurants at that time.

He then noted that the bottles in the library were unlabelled, as is common when keeping wines at the domaine. Ponsot agreed to this. Mooney then said that once they label a bottle, they become liable to tax on it under French law, which M Ponsot negated. The bottles are labelled when they leave the vineyard, and Ponsot contradicted Mooney’s assumption that this would not be done if passing to a friend, or sharing one with the family.

Mooney then turned his attention to the strip labels and import stickers, and Laurent Ponsot confirmed that Domaine Ponsot did not add these – they would be added by the importer to whom Domaine Ponsot had sold the wine. The strip labels and import stickers on the exhibits shown were wrong because they related to the wrong period – for example the Frank Schoonmaker wines were too late for that label – or because they had never used that importer.

Ponsot confirmed that they did not put serial numbers on their wine before vintage 2007 (which would have been bottled and labelled, of course, after Laurent Ponsot discovered the fakes in the AMC April 08 auction). He also confirmed they did not use wax before 1985, and that this was only done on the old bottles that had been refilled and recorked to store in the library. The rest had foil capsules. So something sold out of the Domaine from the library from a pre-1970 vintage would have foil, Ponsot agreed, but he disagreed that there were many of these. He reminded Mooney that they had relatively few bottles, and so try to keep the ones they have to drink with the family or friends. He had done one auction of some of these wines, including two Methuselahs, at Sotheby’s in February 2000. These all had special labels.

In response to Mooney’s question, Ponsot said they did not recondition or recork wines for other people. He would authenticate it but would not recondition it.

They then looked at the capsules, where these had been cut. Ponsot said that there is no reason to cut the capsule from the bottom, except to look at the cork. This can be for authentication, but it can also be to see if the cork is marked – and if the cork is not marked, someone wanting to fake a wine could use that bottle for something else. Since 1986 Domaine Ponsot has used the name, the appellation and the vintage on its corks; before that it had only Domaine Ponsot. Ponsot was not sure if there were any markings in 1932 – as he said, back then, people were not expecting the wines to be faked.

Mooney said that a non-branded cork from 1959 would not necessarily, therefore, indicate a fake. Ponsot replied that this wine could not be a Clos Saint-Denis because that wine did not exist at that time, cork or no cork. Mooney queried whether the vineyard itself existed before 1982, and Laurent Ponsot confirmed that it did, and that the vines they had were planted in 1905.

Mooney then asked when Laurent Ponsot was born, and remarked that in 1958, when his grandfather retired, he would have only been four years old, and could not, therefore, be certain that every label had been hand-signed by him for every vintage.

Mooney then reminded Ponsot that he had said Domaine Ponsot never sold to Nicolas, and asked if they sold to Remoissenet – which Ponsot denied. When asked which negociants they did sell to, he replied that Domaine Ponsot did not sell to negociants, but to wine merchants. Mooney queried this, saying that he thought Laurent Ponsot had said they sold to negociants before 1932. Ponsot replied he had not said that – another branch of the family had restaurants and the wine producers sold barrels of wine to the restaurants of the family, which were railway station restaurants in Northern Italy. The restaurants would then have bottled it to sell to their clients.

Mooney then queried why Ponsot had said on previous occasions that the estate started domaine bottling in 1934, and now he was saying 1932. Ponsot replied that he had previously relied on what his father had told him, but that when he dug into the family archives, he discovered it was 1932, and they discovered a bottle from 1932 in the cellar of a restaurant that the Domaine used to sell to. Mooney commented that Hippolyte Ponsot was something of a Renaissance man, not one to be bothered with lots of paperwork necessarily.

Mooney asked if, even though the Domaine does not do recorking, if someone could do it themselves. Ponsot replied that he had never heard of that, nor of people adding wax to protect their wines. If he had a bottle that was, for example, leaking in the Domaine library, he would check the cork, and maybe change it, and potentially re-wax it. But he would never do that to a bottle in his own private cellar.

Mooney asked when Laurent Ponsot had first learned of fake Domaine Ponsot bottles, and Ponsot replied that the first was in Kuala Lumpur in 1995, but that this one was a bad fake, with a photocopied label. From that point he would see one, maybe two bottles at a time, from time to time; the AMC April 2008 auction was the first time Ponsot had seen so many fake bottles. He acknowledged that he had been told that Kurniawan agreed to pull the bottles. Mooney then said that Kurniawan told Laurent Ponsot that he got the bottles from a single source. Ponsot contradicted him, saying that Kurniawan did not say anything about the source of the wines then, but said that he would send M Ponsot the information. Kurniawan did send an email, saying he had bought the wines from Pak Hendra in Asia, which was all the information provided.

Mooney suggested that when Laurent Ponsot arranged to meet Rudy Kurniawan in July 2008, Kurniawan seemed happy about this. Ponsot replied that he was not focused on Kurniawan; he was just trying to find out more. Mooney noted that Ponsot had not brought any wines with him, but that Kurniawan brought two bottles, a 1975 white Ponsot and a Richebourg. Ponsot replied he didn’t remember which wines – Kurniawan had brought many, and Ponsot did not want to drink all of them. They picked a 1955 La Tâche. Mooney asked if this was the dinner at which Kurniawan wrote down the telephone number, and then queried whether Ponsot was absolutely sure that it was not his own handwriting, whether he had copied the number down after Kurniawan gave it to him.

Mooney asked whether M Ponsot had asked for Pak Hendra’s first name. Ponsot replied that he thought it was Pak. Mooney said that for sure this was not a first name, to which Ponsot replied that he didn’t know, as he didn’t speak fluent Indonesian.

Mooney then asked if there were conversations at the July 2008 dinner about Kurniawan buying directly from the Domaine. Ponsot said there were not – it was not that he didn’t remember them; the issue was not discussed. Mooney then asked if there were conversations about Kurniawan buying for distribution in Asia. Again, Ponsot replied this was not discussed.

Mooney asked if when the numbers were written down, Ponsot was surprised at Kurniawan being able to just write them down like that. Ponsot replied he was not surprised at anything. He did not remember if Kurniawan had had to check a cell phone or a notebook, and it absolutely was Rudy Kurniawan and not anyone else who wrote the numbers down.

Mooney then asked whether, when Ponsot called the number, anyone answered saying “Lion Air”. Ponsot said that one was a fax machine, and the other was never answered. (Doesn’t say much for Lion Air’s purported customer service….) He agreed that no one tried to sell him airline tickets.

They then discussed the dinner that Laurent Ponsot and Rudy Kurniawan had in May 2009. To this dinner, at Fourteen in Los Angeles, Kurniawan brought two different 1973 Ponsot Clos de la Roches. They sampled them both, and decided that one was real, which Ponsot agreed. Mooney said they had questions about the other; Ponsot replied that there were no questions – it was not real. Kurniawan had told Laurent Ponsot that he would bring two bottles, because he thought that one might be fake; Kurniawan said that he buys a lot of wine, and can be fooled by some providers, and wanted to check these out.

Ponsot agreed with Mooney that by this time he had started to become very active in trying to police some of the counterfeit wine problems that were going on, and had stated openly that 80% of pre-1980s wine from the four main domaines of Burgundy (Ponsot, Rousseau, Roumier and Romanée-Conti) were fakes. He has spoken to the heads of the wine departments at Christies and Sotheby’s, who were willing to help. For example, at a recent auction in Hong Kong by Christies, each bottle had a code that identifies the cellar of the person selling the wine. It doesn’t mean the bottle was not fake, but it does identify the provenance if it is shown to be fake.

Mooney then spoke about the Asian market, the rise of Hong Kong as an auction market since the abolition of wine taxes, and the common practice of giving wine as a gift in Asia. Ponsot replied he did not know about that. Mooney then commented that the dinner with Kurniawan in Los Angeles in 2009 “was still a friendly sort of dinner, wasn’t it?”, to which Ponsot replied “It was?”

Mooney then asked if Ponsot had by that time discovered that Kurniawan was from Indonesia, and whether he had considered that Indonesia can be a bit of a scary place, and that Kurniawan might be scared to tell him any more than he had already done. (Side note: this is an interesting line of questioning. To my mind, and it does not at all excuse Rudy, I am absolutely certain that if he were not so scared of someone, he could have got a far better deal by plea bargaining.) Ponsot said he did not think that Kurniawan was scared.

Laurent Ponsot, re-direct

Jason Hernandez asked Laurent Ponsot about the statement he had made that as much as 80% of pre-1980 Burgundy from the four most significant domains could be fake, and when he came to that opinion. Ponsot replied that once he started investigating, he collected the most examples possible of wine sold at auctions in the last 20 years. He saw, for example, that four times as many magnums of 1959 Rousseau were sold in this period as were actually produced, and while one magnum may be resold two or three times, it makes a lot of magnums still alive today from his grandfather’s or father’s time. He also knows that they produced three barrels of 1945 Romanée-Conti, and at each auction one or two bottles or magnums – that just doesn’t happen.

Ponsot added that,

“Wine is not a beverage…. Wine is the best cement of diplomacy and friendship. And when you own a bottle which is rare and good, you are tempted to drink it with your friends or with your relatives rather than to sell it. And today, unfortunately, I say that, from my point of view, too many people are buying wines to speculate on it. And this is not a good thing. It comes to the point that these wines cannot be a tool, but it’s a product between people.”

He thought that the real problem started in the late 90s, early 2000s, with the advent of very rich people from newly open markets in Asia, Russia and America, who were not willing to go into the culture of wine. Because they were wealthy, they wanted to buy the best, and so they read books and found critics who told them that the best wines were the oldest Burgundies. The problem is that these wines exist only in very small quantities, if at all, so some very smart people decided to produce them.

Ponsot was excused, and remained to watch the rest of the proceedings.

Click here for Part 4.